Changing Voices:

Christopher Barzak and Matthew Cheney in Conversation

May 2024

Christopher Barzak and I have known each other for a couple decades, having met originally when, if I remember correctly, he wrote to thank me for saying nice things about his story “The Blue Egg” in a post on my Mumpsimus blog in January 2004 (“beautiful and elegant and poignant” — a description applicable to everything he’s written since). I still remember the feeling of first reading that story and thinking, “I wish I was cool enough to be friends with this writer.” That he then wrote to me felt like a weird coincidence, a nice bit of magic.

I never got cool, but I did become quick friends with Chris, and it’s been one of the greatest joys of my life to watch him develop as a writer and person. There’s no rule that someone of rare talent and vision is also a kind and thoughtful human being, but Chris embodies all those qualities.

He’s written the novels One for Sorrow, The Love We Share without Knowing, Wonders of the Invisible World, and The Gone Away Place, as well as three story collections: Birds and Birthdays, Before and Afterlives, and Monstrous Alterations. He’s won the Crawford Award for debut fantasy book (One for Sorrow), the Stonewall Honor Award from the American Library Association for Wonders of the Invisible World, and the Shirley Jackson Award for Before and Afterlives, as well as having been nominated for the Nebula Award four times, among others. One for Sorrow was filmed in 2014 as Jamie Marks Is Dead (directed by Carter Smith) and The Gone Away Place was adapted for stage by the Youngstown Playhouse Youth Theatre.

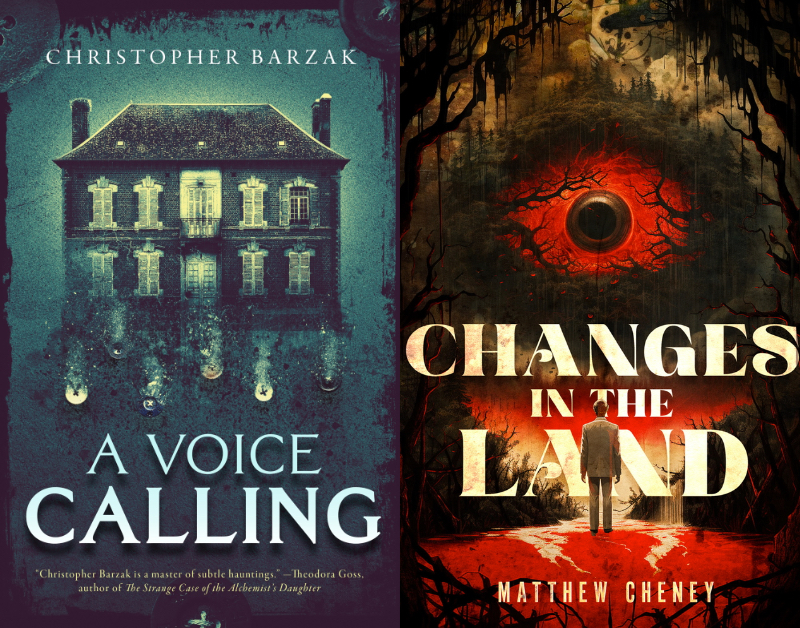

For all those accomplishments — and that’s just a brief summary of highlights — Chris had not published a novella until this year. A Voice Calling is the first novella from Psychopomp, and it’s a richly affecting expansion of Chris’s story “What We Know About the Lost Families of —— House”, originally published in Interfictions (where my story “A Map of the Everywhere” also first appeared).

Changes in the Land is my own first published novella, and it was released by Lethe Press, who published Chris’s collections Before and Afterlives and Monstrous Alterations. Since our books were coming out within weeks of each other, we thought it might be fun to talk about them together, about how we both happened to come to novella writing after a lot of time writing other things, and about the idea of novellas generally.

Matthew Cheney: Let’s start generally. What’s your relationship to novellas as a reader? Is it a form you’ve long been aware of? One you seek out? Avoid? Don’t notice?

Christopher Barzak: As a reader, I’ve always loved novellas. They possess the concision of the short story with the expansiveness of a traditional novel, which allows for readers to experience some of the effects of both forms in one place. I like that readers can get to explore ideas and characters at length without the fuss of multiple and unnecessary side plots.

I’ve been aware of the form since I was a teenager, but it was almost an extinct form after the many years that the print publishing industry stopped printing them because they took up too much space in magazines, which isn’t a good thing for magazines, which need to have as many authors as possible on their table of contents, drawing their various audiences to buy and read the magazine. When magazine editors print a novella, it will generally take up a third of the pages for a given issue, maybe more, depending on its length. So it became a very rare length of fiction to find over the years because of this materially practical problem. There was nothing ever wrong with the novella form itself, just its practicalities for print publishing magazine culture. And of course the publishing industry itself has a self-fulfilling prophecy that readers don’t want to buy or read ANYTHING other than novels, which we know isn’t true. Now if only industry leaders would recognize that instead of ushering in the early deaths of other forms of literature.

Do you still remember the first novella you read? Mine was A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens (which is still a favorite of mine). Then, not long after, I read Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and then Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. I think the form is perfect for readers who want the immersive effects in a novel, but with the focus that the form of the short story offers.

MC: For me, as with so much, it all goes back to Stephen King. Different Seasons taught me what a novella was. I don’t think King uses the term “novella” is his afterword to the book, but he does talk about stories over 20,000 words and under 40,000 words being impossible to sell. I loved that book, “The Body” especially (because I adored Stand By Me, and my copy of the book is the movie tie-in paperback, now crumpled and yellowed and beautified by age). I think the first writer I really thought of as a “novella writer” — as in, somebody who really shined in the form — was Lucius Shepard. I subscribed to Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, and stories like “The Scalehunter’s Beautiful Daughter” (still a favorite) really captured my heart.

Though I am generally pessimistic about the contemporary landscape for publishing, I am heartened by what feels like a growth in opportunities for novellas to be published. Yours is the inaugural release for a novella series from Psychopomp. I know other small presses that are releasing novellas either just as regular releases or as part of a novella-specific series. It’s new enough that when Steve Berman at Lethe asked me last summer what I’d been working on recently, I replied, “A novella I’ll never find a publisher for,” and Steve immediately said: “Send it to me! Small books are selling!” I had actually never thought Changes in the Land had the heft to be a book of its own — I’d been planning for it to be in a next collection, if I have one — but now it’s been published on its own, I can’t really think of it otherwise.

Let’s talk about the writing, then. A Voice Calling is your first published novella, but the first draft of it goes way back. Have there been others? What differences do you feel in writing novellas as opposed to novels and short stories?

CB: A Voice Calling is my first and only novella. I wrote the first draft of it nearly twenty years ago. I then showed it to some of my then writing mentors, who thought it was really good, but who worried that because the novella market was so small, it might be difficult for me to find publication for it. Along with the small market for them at the time, even within that market–at least within the speculative fiction magazine industry–those rare spots for novellas tended to go to well known authors with legions of fans. Because of those two factors, I ended up turning A Voice Calling into a short story (titled: “What We Know About the Lost Families of – House”) and publishing it in the first volume of an anthology series called Interfictions, edited by Delia Sherman and Theodora Goss. Then, as usual, I moved on to other things. I didn’t write another novella because it seemed pointless to do so if I wouldn’t have opportunities to publish them. Then, as the ebook revolution occurred, the novella market began to revive. It turns out that readers don’t make as much of a fuss about the length of a narrative as publishing insiders do.

What differences do I feel in writing a novella versus a novel? Relief that it won’t take as long to write (he said glibly). Differences between writing the novella versus the short story? Relief that I can explore a bit more instead of closing doors as I move through the corridors of the story.

What about you? Do you find anything strikingly different between writing a novella versus a novel or a short story?

MC: Until Changes in the Land, I had only written a couple of really boring, baggy novellas, things no revision could save. They were useful writing exercises, but I think the mistake I made was thinking of novellas as different in the writing from short stories. (They are different from novels … but I say that as someone who’s only written two, unpublished, novels, so take it with a grain of salt.) Changes in the Land began as a short story. I thought I was writing a 4,000- to 6,000-word story. I did write that, then shared it with a friend, Richard Larson (to whom the novella is dedicated), who said, “It feels like there is more here.” And there was. As I kept seeking out that more, digging in, it all began to find its form. I still think of it as a long short story, though!

I tend to conceptualize in the short story form and then, after great reluctance and a period of denial, allow myself to think of them in longer formats if the short story form begins to feel like it won’t let me do some of the things the story is calling me to do.

CB: I think I know what you mean when you say you still think of it as a long short story, especially if it started out as one, had that shape and form in your mind initially and for a while. I think when a story starts to grow and take on a different form and shape, no matter how long it gets, I still think of it as the short story I had probably envisioned it as initially. I tend to conceptualize in the short story form and then, after great reluctance and a period of denial, allow myself to think of them in longer formats if the short story form begins to feel like it won’t let me do some of the things the story is calling me to do. It’s so difficult to leave behind the idea of the short story. They seem so much more doable. As soon as I realize something may take more than fifty pages, I begin to fret, realizing how much of a commitment it will be to take a long story on.

MC: Endless fretting! But if we’re lucky, now and then a structure presents itself. In fact, one of the things I love about A Voice Calling is the structure and how in the middle it’s suddenly different from the short story version. You essentially created a story-within-the-story, yet it’s also the story. Was the structure there in your old notes, or was that something dreamed up by the more experienced writer you are now?

CB: So, as you mentioned, I reconstructed this novella from notes I had on the novella, as I’d lost the original manuscript somewhere between moving to Japan and coming home from Japan. I think I may have accidentally deleted the novella version at some point. But I did have about ten pages of notes on the novella, handwritten, and I reconstructed it from those. No, the structure wasn’t a part of those notes. And in my memory, the old version of the novella stayed in line with the chaptering cadence that I established for the short story version, which was brief chapters of 4 or 5 pages, somewhat out of time linearly. When I began to work on reconstructing the novella, I decided not to work within that structural aesthetic and to instead allow the story within the story to have its own space. It’s a kind of structural trick that I’ve enjoyed in the novellas of A.S. Byatt. like The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye. or any of Isak Dinesen’s Seven Gothic Tales, or Angela Carter’s work. I felt, too, that the novella was going to examine one of the ghosts that inhabit Button House very specifically, not all of them, and so that chapter, the story within the story, is focused entirely on her. I didn’t want to break any of that up, like the other parts of the narrative, which is more fragmentary.

MC: It works so beautifully because it disrupts our expectations. When I read it, I wasn’t looking ahead, I was assuming this new chapter would be as short as the others, and then it kept going, but by the time I realized that, I was in this story and very much wanted it to keep going. Also, since I knew “What We Know About the Lost Families of – House”, I was really interested to get to spend time with one of the women who becomes so important to the events, but couldn’t be important in a short story if the story were to stay short. But I do feel like that choice is the choice of a mature writer, somebody with some experience, some trust to just break apart the structure and do what the story needs.

CB: You have something similar happening in Changes in the Land, in that there’s the “front narrative” but also this story within the story happening in the research report and academic notes that litter the novella. How did you find managing moving between direct narrative and an inhabited form like an academic report with footnotes? I always love stories that employ this structural maneuver, but it seems really challenging, having not attempted it myself, and despite working in academia for two decades.

MC: The structure of Changes in the Land was a complete accident. I set myself the challenge I mentioned of writing a super-compressed story. I did a bunch of work on the backstory, creating timelines, histories of characters, all sorts of stuff I deliberately tried to keep out of the story. Iceberg theory and all of that. But then it was just … flat. It was a first draft of some of what is now that front story. The character of Steven Baird, the academic, only came in at the end, and there was no way for any reader to care about his fate because they didn’t know him. I decided that I needed to know him better myself, so I thought I’d write a diary for him. This was nothing I ever intended to put into the story, it was just for me. I wrote it super quickly as an actor would who was doing character work before performing in a movie or play. Totally unselfconscious because it was just for me. It got up to something like 15,000 words. Then I thought about putting some sentences from the diary in between what I already had — still thinking of this as a short story, though now of maybe 6,000 to 8,000 words — and I liked the effect, so I just kept going. I expected first readers to say it was boring and all needed to be cut. Instead, they encouraged me to add more. I was so focused on the content of the material that I hadn’t realized its real value was in developing character. For readers who like details, the details are there (footnotes!), but their primary purpose is to demonstrate how Steven Baird thinks and why his life is what it is.

Though it took an awful lot of trial and error, I enjoyed writing Changes in the Land and am really interested in trying to write a novella that I actually set out to write, rather than stumbling into it again. What about you? As much as I and other readers yearn for the next Barzak novel or story collection, I think novellas are a wonderful form for you and am hoping you think so as well…

CB: Well, thank you, I’m happy to hear the reading experience for you has made you want to see more novellas from me. I would like to write more novellas, yes, now that there are more opportunities to actually publish them. I really like this space between the short story and the novel, and how you can get the best of both forms by way of it. I’d be remiss, though, if I didn’t mention being able to restore this novella to something like its original form has made me want to explore this story even further, possibly at novel length. But I do have a number of other stories knocking at my door, and there’s the part of me that wants to move forward instead of lingering, so I may try to scratch both itches and write one of my current story ideas at novella length and then, if I’m still interested, move back to the world of A Voice Calling, if it still calls to me.

How about you? Changes in the Land, I thought, really gave you the space to open up so many of the great ideas that you put forth in short stories. Will I be seeing more Matthew Cheney novellas in the future? (I hope so!)

MC: Yes, probably — my short stories for the last ten years have been getting longer and longer, and so I sometimes fantasize about pulling a César Aira and just publishing a bunch of weird little books. Or a series of interconnected novellas. I love what Alice Munro has done with interconnected stories, including novellas. Her book Runaway is an all-time favorite of mine, and the “Juliet stories” in it are just sublime. I also like thinking about how poets organize their collections, which has become a real art. I wonder, for instance, what Jos Charles’s astonishing feeld might suggest for a collection of fictions linked by language, perspective, and theme. Rose Metal Press published a book of “novellas in flash” called My Very End of the Universe and I find that sort of formal experiment excitingly bewildering to think about.

But my obsessions are mostly about memory, point of view, and place, so I probably won’t get too experimental, much as I appreciate writers who do push more against the borders of form. I’d love to try a series where the main character of one story is a background character in others, maybe with a novella bringing it all together. I don’t know. I feel no compulsion to write a traditional novel, but I like making books, like the possibilities in gathering stuff together between covers and calling it a unity. With luck, some publishers will remain interested in taking a chance on such things, and we can all, readers and writers, explore new worlds together…

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.