The Rats in Our Walls: An Essay

We are all lichens.

—Gilbert, Sapp, & Tauber

“A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals”

The Quarterly Review of Biology (87: 4, 2012)

Revisiting H.P. Lovecraft’s story “The Rats in the Walls” recently, I couldn’t help but think of QAnon and the “Great Replacement theory” and other nuttiness from rat-bit racists, ideas so flagrantly stupid that I keep expecting a revelation that the American rightwing is actually some sort of long-con Andy Kaufmann performance. Alas, it’s no joke. The discourse has deadly results.

While contemporary rightwing ideology is vapid, ridiculous, cruel, and murderous, it is also an unabashed retreading of old-time bigotry. Much as the right’s war against queers makes it feel like we’re back in the 1980s and 1990s, so too does the blatantly racist nativism of the MAGA monsters make it seem like we haven’t gotten far beyond March 1924, when “The Rats in the Walls” appeared in the pages of Weird Tales and led its readers toward a vivid denoument premised on fears of human devolution and degeneracy.

I am hardly the only person to notice this. In an essay on Lovecraft for The New Republic in March 2021, Siddhartha Deb writes:

We live, once again, in a world rendered frenetic by its own success. In the post–Cold War era, the West and the Western way of capitalism are seemingly triumphant. A passport from a G7 country signals membership in the upper tier of humanity; one from a “failed state” is tantamount to a death certificate when attempting to cross borders. Yet, as the eruptions of Trump and Brexit, the armed gathering of self-described “Western chauvinists” the Proud Boys, and clusters of adult males from the United States, the U.K., Canada, Australia, and Germany on 4chan make apparent, a significant number of people feel once again that the West and white nationalism are under threat. Even the books promoting these views sound the same as they did a century ago: bestsellers like Patrick Buchanan’s The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization, Jonah Goldberg’s Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Nationalism, and Socialism Is Destroying American Democracy, and pretty much everything from Charles Murray and Samuel Huntington.

In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Donna Haraway says (with a cleverness both impressive and cloying), “It matters what thoughts think thoughts. It matters what knowledges know knowledges. It matters what relations relate relations. It matters what worlds world worlds. It matters what stories tell stories.”

Haraway’s Chthuluscene is not Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythography. She dismisses Lovecraft in a sentence. Her word is neologized from two Greek roots: khtōn (earth, ground, soil, world, land, country) and kainos (new, recent, fresh, unusual) to create a term she says names “a kind of timeplace for learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying in response-ability on a damaged earth. Kainos means now, a time of beginnings, a time for ongoing, for freshness.” Chthuluscene is opposed to the Anthropocene or Capitaloscene, terms Haraway finds too anthropocentric, too fatalistic, incomplete. “Living-with and dying-with each other potently in the Chthuluscene,” she says, “can be a fierce reply to the dictates of both Anthropos and Capital.”

I invoke Haraway both because I am partial to her vision of an entangled existence within the symbioses of hologenomes and holobionts (it makes me think of a personal touchstone, Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid) and because my perverse mind wonders if we might reterritorialize Cthulhu into the Chthuluscene.

Reterritorialization first requires deterritorialization — uprooting. To uproot, we must dig in the soil, the mud, the muck. (With Lovecraft and some of the associated topics here, there is plenty of muck.) But we’ve got to find the roots so we can see which ones are, despite rocks and rot, healthy … and which need to be cut away.

This will be a journey.

Part One

It is the racist who creates the inferiorized.

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

trans. Richard Philcox

Rats in the Narration

Too often, especially among readers who want stories that (in Jen Silverman’s words) provide moral guidance, we try to read Lovecraft’s narrators as if they are rational and as if our only option is either to read them as prophets or reject their “message”. Lovecraft’s fiction is not moral guidance. Lovecraft’s fiction is full of guano-spewing whackadoodle nutballs. Because of those nutballs (not despite them), Lovecraft’s fiction is narratively more complex than it usually gets credit for. When we read these characters as portraits of insanity clothing itself in the guise of rationality, Lovecraft’s stories open themselves up to a compelling variety of possibilities.

For instance, in “The Rats in the Walls”. Consider what happens if we start from the fact that the narrator, Delapore, is an inmate of the Hanwell Asylum. What if we read the story not as a story first published in Weird Tales but rather as a testament by a mental patient — someone who, let’s say, suffers severe paranoid delusions. We do not have to read Lovecraft’s narrators as rational men who encounter unspeakable horrors that make them go mad. Instead, we can see them as people who perceive themselves to be rational, but we, standing outside their obsessions, can see how their ideologies and fears debilitate and delude them. We can read the stories not so much as tales of objective horror but rather as tales of the perception of horror.

Reading a story like “The Rats in the Walls” as the ravings of someone without a clear sense of reality destabilizes the text, even though the text literally tells us that the character is a mental patient. Genre conventions train us to see madness in such stories as vision. The question we should ask about any of Lovecraft’s narrators, though, is where does the narrator’s perception of reality diverge from a consensus reality, whether the consensus reality of the characters in the text or the consensus reality of the reader? That determination of reality is the problem of any radically unreliable narrator poses to readers … but it is also the problem embodied by anyone whose mind has been given over to bigotry and conspiracies. Where does reality end and the delusion begin? In this way, Lovecraft’s narrators pose for us an epistemological problem that is as up to date as the latest news cycle.

One of the challenges of a supernatural or weird story is that we must not only decide what is likely real vs. what is likely the narrator’s perhaps compromised perception, but we must do so within a context where what is real in the story is not real in our own world. Let’s start with this sentence from the beginning of “The Rats in the Walls”:

I can recall that fire today as I saw it then at the age of seven, with the Federal soldiers shouting, the women screaming, and the negroes howling and praying.

That sentence is one that we should interpret differently than the narrator likely does — assuming the story is set in, more or less, our own historical reality we can make a good, educated guess that “the negroes” there are enslaved people probably pretty excited to see their enslavers’ home getting destroyed — but the interpretive difference between us and the narrator is a difference in the interpretation of history. The sentence could appear in any historical novel about the Civil War. It could conceivably even appear in a historical testimony. It is valuable to recognize that that sentence cries out for an interpretation that may not be the narrator’s interpretation, but it does not require us to make a determination of whether it fits with our understanding of the possible and impossible, real and unreal, natural and supernatural.

What, though, do we do with these sentences:

The quadruped things—with their occasional recruits from the biped class—had been kept in stone pens, out of which they must have broken in their last delirium of hunger or rat-fear. There had been great herds of them, evidently fattened on the coarse vegetables whose remains could be found as a sort of poisonous ensilage at the bottom of huge stone bins older than Rome.

This poses a far greater challenge for reading with skepticism toward the narrator, because by this point we either have to accept that there is a twilit grotto full of horrors or we have to decide it is some sort of delusion. If delusion, what sort? Is there a grotto but no horrors? Is the delusion shared by Norrys or Sir William or any of the other people Delapore says accompanied him?

Since the text itself does not have enough clues to resolve those questions, any useful answers ought to be ones that provide a fulfilling interpretation of the story, opening its meanings and resonances. We don’t need to fall into the trap of asking “How many children had Lady Macbeth?” But to ask questions about where the narrator’s perception of reality, the story’s proposed reality, and the reader’s understanding of reality intersect and diverge is still reasonable, because they are the questions fiction always asks us. Fiction of any sort poses the question: What is made up, what is not, and what do you want to believe? All fiction, regardless of genre, requires readers to decide where the limits of fictionality reside, though such a decision is inevitably affected by the perception of genre — if I perceive a story to be a work of realism set in my own idea of reality I will read it differently from a story I perceive to be set in a world of fantasy; if I am told a text is the transcribed ravings of a lunatic, I will read it differently from a text I am told was published in a pulp magazine. (I’ve written in some detail about fiction and its limits in Modernist Crisis and the Pedagogy of Form.)

Narrator / Story / Reader

What I have sketched here is a triple-decker model of a text’s realities — narrator / story / reader. (I am not remotely original in proposing this model. Something similar is likely to come up in any analysis of unreliability and narration. Wayne Booth’s concept of the implied author is one place to start for anybody who wants to go into more narratological depth. In a different way, Stuart Hall’s “encoding/decoding” model might also be useful here, particularly the concept of dominant, negotiated, and oppositional positions for decoding.) Such a model is especially useful for Lovecraft’s work because the act of narration itself is so important to his tales.

The narrator of “The Rats in the Walls” (Delapore) seems to believe in both the “twilit grotto” and “the quadruped things”. (We don’t gain much interpretively if we choose to see Delapore as a con artist attempting to sell us an idea he doesn’t himself believe in.) I expect the author also thought of this as the base reality for the story, because in many ways, that base reality is what makes “The Rats in the Walls” capital-W Weird. Let’s see what happens, though, when we try a thought experiment. Let’s see what happens when we read “The Rats in the Walls” less as a weird tale and more as the tale of someone who thinks he is living in a weird tale.

As readers, we can decide that the base reality of the story is closer to our own and farther from the imagined one Lovecraft proposes. After all, the reality Lovecraft proposes is based on racist ideas of heredity. We don’t need to accept that reality. We are free to make the reality of the story into a site of contestation between the narrator and the reader.

There is, I think, an interesting story to be had from “The Rats in the Walls” if we assume that the vast majority of what Delapore tells us is in his addled mind, not in the reality around him. Reading “The Rats in the Walls” as entirely delusional turns the story into a case study of a fevered, racist mind.

Interpreting such stories as delusional monologues works against the grain of the tales themselves, which Lovecraft deliberately, intentionally wrote as weird fiction. We remove a big part of the “cosmic horror” of the later stories especially if we don’t read them as presenting a vision of the actual universe but instead as visions dreamed by frightfully insane people. Nonetheless, I still find the stories compelling if I believe their narrators are nuts. I read them in the way I read Lovecraft’s letters, which, like all of his writings, are the work of a uniquely bizarre, obsessed, passionate, pitiable man. That complexity and contradiction is especially human, and the human is interesting. As the queer punk Mormon Lovecraftian W.H. Pugmire once said, “Lovecraft the man comes fully alive in his correspondence,” and because he comes so fully alive with contradictions and yearnings and obvious failures alongside moments of brilliance, I find it easy to reject his ideas (I don’t think he was much of a philosopher) but impossible to detest him, even when he is ranting for pages at James Morton about the necessity of eugenics programs and the inferiority of everyone who is not a blond, blue-eyed Aryan, and literally ending his letters with the words “Heil Hitler!”

Reading such passages — pages and pages of baroque justifications for white supremacy, written to a friend he respected but who was trying to get him to be less of a bigot — what we see is a man putting every bit of intellectual energy he has into building a structure to pull himself up so that he can feel less ugly, less doomed, less pathetic. Perhaps this is part of the reason why Lovecraft has remained so attractive to weird people he himself would have considered degenerate, people who, like him, feel like outsiders for some reason or another. Indeed, so many of his own friends were exactly the sorts of people he thought should not be procreating. (Though I don’t know that he ever actually knew any black people. This may be one of the reasons why he always separated them out as the most unredeemable, the least human, in his grand taxonomy.) Lovecraft was intellectually debilitated by his commitment to hierarchies, his need to sort everything into degrees of better and worse, but his sense of alienation is bigger than this, more expansive (cosmic!), and it is that sense that still resonates. Even more than the letters, the stories reveal a sensibility aching to be freed from its prejudices, its limitations, its self-loathing and sadness.

Alongside horror in Lovecraft there is also yearning, and in the best of his writing, the yearning and horror are symbiotic.

Lurking Fears

While reading Lovecraft’s first-person narrators as delusional men fueled by the fever of their own bigotry makes the stories in many ways unsettling and compelling, I can’t help but want to preserve some of the weirdness within those stories. How, though, do we preserve that weirdness when it is based in a fundamentally racist concept like degeneration?

Degeneration is an old idea. In a 1986 essay in The Georgia Review, R.B. Kershner, Jr. describes its deep history:

Degeneration was not simply—or even mainly—a stepchild of Darwinism, although without Darwin it would have lost much of its force and immediacy. As a general term it had been in currency at least since the sixteenth century, often harnessed to a Christian context. The word connoted a falling off from ancestral or original excellence, so that Thomas Taylor could speak of the times “when men degenerate, and by sinne put off the nature of man” (1612 ). Yet simultaneously, the word retained a biological implication, as when, in the eighteenth century, wheat was thought to degenerate into darnel. Thus the word’s genealogy already included an ambiguity between an assumed physical process and a moral evaluation when, in the nineteenth century, degeneration became a term with social significance.

In an incisive essay titled “The Shadow over ‘The Lurking Fear’”, Michael Cisco gives us one way through the challenge of Lovecraft’s narrators: “The repulsion of horror in Lovecraft is often associated with a desire that coexists alongside it.” Cisco points out that in Lovecraft’s stories, the narrators frequently end up rejecting what, if we use Lovecraft’s own tastes as a guide, they should be expected to embrace. “The Shadow over Innsmouth” is a particularly clear example, as Cisco says:

The sea dwellers are not mindless monsters; they have a civilization of their own, with a magnificent city and refined artistic tradition, of which the tiara is an example. Their culture is ancient, sophisticated, unvarying, a Lovecraftian utopia in certain ways. Lovecraft doesn’t do more than hint about it and most likely did not have any developed idea of that culture; the point is sufficiently achieved for his purposes by those hints. That point is: belonging to this fantastic lineage is, however initially horrifying to contemplate, actually a kind of promotion from the level of the merely human. This abrupt inversion in point of view is clearly meant to be an aspect of the fearful transformation of the narrator, but why then should every such transformation involve the realization of Lovecraft’s values? Here, the horror transforms into an all-too-understandable ambition right before our eyes.

This allows some differentiation between horrors in Lovecraft. Cisco writes of the 1922 story “The Lurking Fear” and its monsters in the Catskills: “They are all but purely beasts and bear a far stronger resemblance to the merely degenerate throngs of modern city dwellers Lovecraft described in ‘The Horror at Red Hook,’ and in his racist diatribes, than to the always subtly majestic ancient or attractive beings of his other stories.” In an essay on Lovecraft’s narrators, R. Boerem notes that “The Shadow over Innsmouth” represents “a change in the experiencing of horror for Lovecraft’s narrator-protagonists, who begin by fearing what is outside of themselves, to fearing what is inside of themselves or what they themselves have become, to accepting what they have become.”

In the later stories, the narrators’ fears can seem disproportional, and the evidence in the texts suggests that these are narrators who are so conditioned to fear that they are incapable of feeling the more generous,open, and awe-struck emotions someone else might feel in their situation. In “The Shadow Out of Time”, for instance, I find it difficult to understand the narrator’s bone-deep terror, when it seems like what he ought to be feeling is wonder and awe. (A conventional science fiction writer — like the people whose stories were printed on the other pages of the issues of Astounding where Lovecraft’s late stories first appeared — would have given us sturdy, adventurous men devoted to the sense of wonder.) The terror makes little sense unless and until we recognize Nathaniel Peaslee as clinging to the idea that humans are the best and greatest beings in the universe, and therefore he suffers when presented with the idea that humans are, in fact, inconsequential. Time itself seems to give him pain and terror. “It is a matter of hundreds of thousands of years — or heaven knows how much more,” he says. “I don’t like to think about it.” Even he briefly recognizes that his terror is overwrought. “I remained awake all that night, but by dawn realised how silly I had been to let the shadow of a myth upset me. Instead of being frightened, I should have had a discoverer’s enthusiasm.”

There are what seem to be legitimate fears in the story, fears that are themselves very old, and have been passed down through folklore for millennia by the aboriginal peoples of Australia. These fears Peaslee doesn’t take seriously enough because his prejudices prevent him from doing so (what, he thinks, could superstitious indigenous people know, really?). The text seems quite clear on this point. If Peaslee is not completely delusional, then the one thing he really ought to fear is the wind, which seems to originate from the elder creatures locked deep beneath the Great Race’s ruins. Like anybody might be who was imprisoned for a few hundred thousand years, those elder creatures are likely to be pretty bitter and vindictive when they get free. A prospect deserving of anxiety. But the Great Race creatures didn’t mean Peaslee any harm, they were just avid collectors of knowledge who happened to discover how to project their minds into other bodies across time.

That all comes later, though. In the stories from the early 1920s, we’re dealing with less complex narratives.

With “The Rats in the Walls”, we should be careful to consider its portrait of aristocracy. If we do not assume Delapore is completely delusional, and go instead in the opposite direction of reading his testimony as completely accurate, then what we have is, yes, a racist idea of degeneracy — but also one that portrays a rot at the heart of aristocracy. I don’t think we are obligated to interpret that rot in the way Lovecraft himself undoubtedly did. Instead, we could look at what the twilit grotto reveals and see the deep corruption of power that we might find in any aristocratic lineage alongside a metaphorical reminder that, for all their fine airs and wealth, members of rich families come from the same primordial ooze as the rest of us.

If anything, the grotto reveals the folly of seeking wonder and glory in ancestry.

Part Two

He was right: us against them.

Except they are us.

—Diary of the Dead (written & directed by George A. Romero)

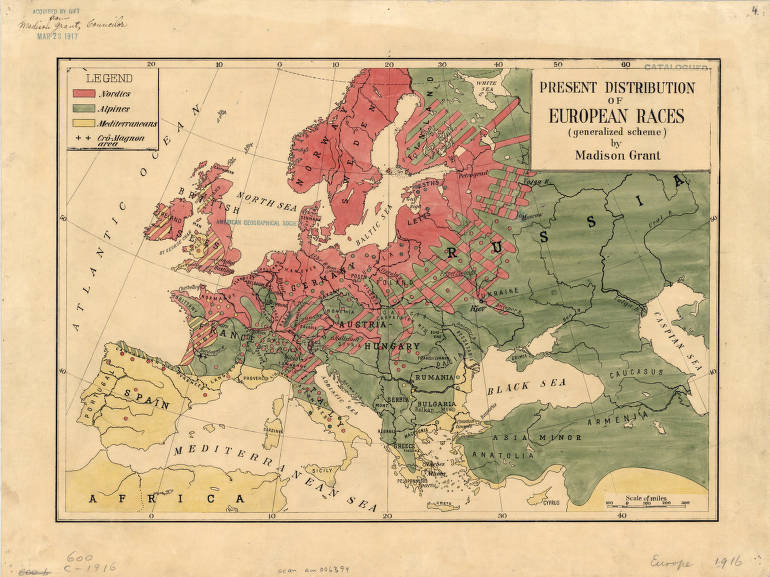

Madison Grant's Great Race

H.P. Lovecraft and Madison Grant died within months of each other in 1937. When they were alive, Grant was vastly more famous than Lovecraft; now, of course, it is reversed. While hardly anyone today knows the name of Madison Grant, Lovecraft’s work is all in print in numerous editions, both his work and life are subjecta of significant study by fans and scholars, and his figure is something of an icon throughout global popular culture.

I have been aware of both men for most of my life. Thanks to a childhood enthusiasm for the writings of Stephen King, I read King’s book about horror, Danse Macabre, quite young, and from it first learned about Lovecraft, though it took a long time for me to learn how to appreciate Lovecraft’s stories. Madison Grant I learned of from my father when we were at a used bookstore in Vermont, where he happened upon a copy of Grant’s long-forgotten 1916 bestseller The Passing of the Great Race for $3 (the price is still written in the book, which I inherited). My father was obsessed with studying Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, and he knew that Grant’s book was a particular favorite of Adolf Hitler, a book the Führer described as “my bible”.

John Higham’s 1955 study Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 remains valuable as an investigation of its topic, and Higham attests to Grant’s importance: “The man who put the pieces together was Madison Grant, intellectually the most important nativist in recent American history. All of the trends in race-thinking converged upon him.”

Like Lovecraft, Grant was obsessed with hierarchy and heredity. In his illuminating book Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant, Jonathan Peter Spiro presents the racial concept of The Passing of the Great Race succinctly: “Grant’s book held that mankind was divided into a series of hierarchically arranged subspecies, with the blond-haired, blue-eyed Nordics at the top of the ethnological pyramid and the other less-worthy races falling into place below the master race.” Grant was a vicious anti-Semite (thus Hitler’s fondness for his writings) but when it came to black people, he often seemed as much befuddled as hateful. Spiro writes: “According to Grant, whites and blacks evolved independently of each other, and only ‘old fashioned’ thinkers still maintained that all humans belonged to the species homo sapiens” (p.242). Grant simply didn’t see black people as human; they were, to him, more like livestock. Though his goals were similarly eliminationist, he didn’t quite hate them in the way he hated Jews; he just didn’t know why they ever aspired to a life better than that of, say, a horse. In his last book, the alternately hilariously absurd and nausea-inducing The Conquest of a Continent, he expressed sadness that evolution had not taken care of African-Americans: “Natural selection … in view of the present vital statistics of the two races, can no longer be relied upon to solve the problem by a gradual elimination of the Negro in America. Comfort has been found in the fall of the ratio of the Negroes to the total population; but their absolute increase goes on just the same.”

Almost all of Grant’s ideas about race, eugenics, and anthropology were borrowed from scientists, intellectuals, and politicians, many of whom were his friends and colleagues. Grant himself was not an originator of ideas, but it wasn’t originality that made him important. He had a singular ability with polemic, an ability to speak to the interests and, especially, the fears of his day. Stephen Jay Gould called The Passing of the Great Race “the most influential tract of American scientific racism.” Grant’s book went through multiple printings in its first year, had a revised second edition by 1918, and had sold a million copies by sometime in the 1920s. Upon receiving the manuscript, Grant’s editor at Scribner’s told Theodore Roosevelt he thought the book to be “one of unusual importance”. That editor was the legendary Maxwell Perkins, who would go on to publish Thomas Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. (In fact, Perkins had a house in Windsor, Vermont, about half an hour south of where my father discovered the copy of The Passing of the Great Race that I now own. Vermont, of course, also has some important Lovecraft sites.) As Spiro notes, after the success of Grant’s book, Scribner’s would publish many more books advocating eugenics, including the work of Grant’s close friend Lothrop Stoddard, who, along with Grant, is clearly alluded to in one of Max Perkins’s later projects for Scribner’s, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

Looking at Grant and Lovecraft together shows the extent to which Lovecraft’s passionate racism was reflected in a certain mainstream of American society and culture during most of Lovecraft’s lifetime — importantly, a mainstream of quasi-aristocrats, exactly the class Lovecraft most envied and aspired to. There were people, even among Lovecraft’s friends and correspondents, who worked against the racism of the age, but in putting Grant and Lovecraft together we can see just how deeply certain prejudices not only affected scientific discourse but, in fact, enabled a pose of scientific rationalism. To be a rational, unsentimental person devoted to the truths of scientific inquiry was to be a eugenicist. It remains important to recognize the extent to which racist and xenophobic ideas coursed through the main currents of science during this era, because those ideas still haunt a lot of the ways we talk about heredity, at least in popular culture.

This brings us back to Lovecraft’s narrators. Referencing an article by Deborah D’Agati on Lovecraft and Sherlock Holmes, Jeff Lacy and Steven J. Zani write, “Lovecraft’s narrators tend to be very rational. … The narrative voices of these empiricists are often so appropriately dry and objective that readers may forget that there is, in fact, a character with a particular worldview narrating the story.” One of the ways Lovecraft signals that his characters are rational, objective empiricists is by aligning them with ideas of race, heredity, and degeneration that Lovecraft and millions of other people associated with the sciences.

Ideas from eugenics infiltrated all sorts of disciplines and discourses during Lovecraft’s lifetime, from rightwing anti-immigration crusaders to leftwing progressives drunk on utopian ideas of perfecting the species. For all its multi-disciplinary insidiousness, Madison Grant’s type of thinking especially took hold within natural science, conservation, and anthropology. These were disciplines rife with quasi-eugenicist theorizing for decades before Grant got passionate about the subject.

Grant didn’t make a connection between breeding and humans until he had been working in wildlife conservation for a while. He was, among many other things, the founding father of the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society) and one of the more important originators of the idea of wildlife conservation, an idea he had promoted vociferously, primarily as a way to conserve big game for hunting. His achievements in conservation were impressive and important to this day. His social status, wealth, organizational acumen, stubbornness, and energy led him to be able to achieve things few other people would have. It helped, too, that his friend Teddy Roosevelt became President for a few years, and shared his passion for hunting and for conserving nature.

After World War Two, Grant’s name all but got erased from the historical record, despite his considerable influence on the landscape (literally) of American society. With the revelation of his admirer Adolph Hitler’s crimes against humanity, few people wanted to associate themselves with Grant’s memory, even as his ideas continued to stumble around in the haunted house of cultural consciousness.

Grant proved easy to forget. When he was alive, he did not seek attention for himself. Spiro explains that while Grant had immense influence in the corridors of power and called many of the country’s most powerful people friends, he worked hard to stay in the background himself, preferring to keep his influence quiet. Even after his first book made him famous, he kept away from the publicity machines. After his death, his relatives destroyed all his personal papers. “Moreover,” Spiro writes, “Grant seems particularly cursed by the gods of history. It is somewhat uncanny the number of fluke accidents that have befallen archival collections that we know at one time contained records relating to Grant.” It wasn’t long after his death that Grant’s ideas about races became, in their overt form, anathema, which might explain why, as Spiro says, “an inordinately large number of Grant’s friends destroyed their personal papers. … Equally frustrating — and certainly more morally egregious — is the fact that Grant’s correspondence with certain key figures who did save their papers has nonetheless ‘disappeared’ from the archives. The boxes are there, but nothing is inside them.”

With this decayed, corroded, and corrupted archival record, Madison Grant could be an occult figure from a Lovecraft story, one of those mysterious purveyors of power whose traces have been excised from the records by both deliberate action and strange coincidence. (What if The Necronomicon is not, in fact, an arcane tome … but instead a book called The Passing of the Great Race…)

Like Lovecraft, Grant was not a scientist himself, but drew from the work of biologists and anthropologists. The preface to The Passing of the Great Race was written by his good friend Henry Fairfield Osborn, longtime president of the American Museum of Natural History and co-founder of the American Eugenics Society. Grant was a popularizer and a polemicist, but while scientists may have scoffed at his lack of scholarly rigor, they still agreed with him. The journal Science gave the 1918 edition of The Passing of the Great Race a mixed review, with the criticism being not of the thesis itself, or the idea that “the Nordic race” is in peril, but rather of the haphazard approach and overly pessimistic point of view (the reviewer asserts faith in the effectiveness of eugenics programs). Spiro identifies Grant, Osborn, Harry H. Laughlin, and Charles Davenport as “the Big Four of scientific racism in the United States”. They all worked closely together, and Davenport was a member of the National Academy of Sciences whose 1911 book Heredity in Relation to Eugenics was a popular text in science classes. Like Lovecraft, these men were propelled by a feeling that a great doom lay ahead.

Higham summarizes the ideas that provided the foundation for Grant’s own sense of doom:

Everywhere Grant saw the ruling race of the western world on the wane yet heedless of its fate because of a “fatuous belief” in the power of environment to alter heredity. In the United States he observed the deterioration going on along two parallel lines: race suicide and reversion. As a result of Mendelian laws, Grant pontificated, we know that different races do not really blend. … In short, a crude interpretation of Mendelian genetics provided the rationale for championing racial purity.

What horrified Grant is not far from what horrified Delapore in “The Rats in the Walls”.

As did many other eugenicists, Grant and Lovecraft both disparaged disagreement as “sentimentalism”, a term rich with implications of soft-mindedness, empty-headedness, and effeminacy. (Ancestor to Trump supporters’ statements about other people’s feelings. Whenever Grant, Lovecraft, et al. describe someone as “sentimental” or a “sentimentalist”, you could replace the term with “snowflake” to get a contemporary resonance.) This idea of sentimentalism connects to the eugenicists’ pose of rationality, a pose that was also enhanced by anti-religious ideas. Both Lovecraft and Grant were anti-Christian for various reasons, Grant primarily because he hated the idea of charity, which he thought allowed the weak to continue when they ought to be left to die. Like Lovecraft, Grant venerated ancient Rome and seemed to see Christianity as an impurity in Roman history, leading to the fall of the empire. “Early ascetic Christianity,” Grant wrote, “played a large part in this decline of the Roman Empire, as it was at the outset the religion of the slave, the meek, and lowly, while Stoicism was the religion of the strong men of the time.” Grant seems to prefer the pre-Christian (but not Jewish!) religions: “Christianity was in sharp contrast to the worship of tribal deities which preceded it, and tended then, as it does now, to break down class and race distinctions. Such distinctions are absolutely essential to the maintenance of race purity in any community when two or more races live side by side.” In the way that contemporary proselytizing atheists decry Christianity (and religion generally) as unscientific, so, too, did Grant see it as such because it countered the “scientific” laws of social darwinism.

Eugenic practices rose to mainstream popularity during a time of great panic about immigration in the United States, and so it is no surprise that Grant and Lovecraft both detested immigration and entwined their overall racism with anti-immigrant ideas. Their descriptions of a New York ravaged by degenerates are similar. Here is a paragraph from The Passing of the Great Race:

As to what the future mixture will be it is evident that in large sections of the country the native American will entirely disappear. He will not intermarry with inferior races, and he cannot compete in the sweat shop and in the street trench with the newcomers. Large cities from the days of Rome, Alexandria, and Byzantium have always been gathering points of diverse races, but New York is becoming a cloaca gentium which will produce many amazing racial hybrids and some ethnic horrors that will be beyond the powers of future anthropologists to unravel.

Here’s Lovecraft, from “The Horror at Red Hook”:

The population is a hopeless tangle and enigma; Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and negro elements impinging upon one another, and fragments of Scandinavian and American belts lying not far distant. It is a babel of sound and filth, and sends out strange cries to answer the lapping of oily waves at its grimy piers and the monstrous organ litanies of the harbour whistles. … From this tangle of material and spiritual putrescence the blasphemies of an hundred dialects assail the sky. Hordes of prowlers reel shouting and singing along the lanes and thoroughfares, occasional furtive hands suddenly extinguish lights and pull down curtains, and swarthy, sin-pitted faces disappear from windows when visitors pick their way through. Policemen despair of order or reform, and seek rather to erect barriers protecting the outside world from the contagion. The clang of the patrol is answered by a kind of spectral silence, and such prisoners as are taken are never communicative. Visible offences are as varied as the local dialects, and run the gamut from the smuggling of rum and prohibited aliens through diverse stages of lawlessness and obscure vice to murder and mutilation in their most abhorrent guises. … The soul of the beast is omnipresent and triumphant, and Red Hook’s legions of blear-eyed, pockmarked youths still chant and curse and howl as they file from abyss to abyss, none knows whence or whither, pushed on by blind laws of biology which they may never understand.

Overall, Lovecraft and Grant’s fears were the same. (Since neither Lovecraft nor Grant hid what they feared, I don’t think there is great need here to go into more detail about this, but for explorations of these fears in Lovecraft through a variety of lenses, see writings by Timothy H. Evans, Mitch Frye, James Goho, Brooks Hefner, Bennett Lovett-Graff, Jed Mayer, Jay McRoy, César Guarde Paz, Sophus A. Reinert, and Benjamin M. Welton.)

I have not encountered evidence that Lovecraft read Grant’s work, but I would be surprised if he were not at least generally familiar with it, given its prominence in American culture during the years of Lovecraft’s writing career. In his comprehensive biography of Lovecraft, I Am Providence, S.T. Joshi discounts the similarities between the two, for a few reasons: Lovecraft’s racism was certainly well established before the publication of The Passing of the Great Race, Grant was more consistently committed to a tripartite Nordic/Alpine/Mediterranean idea of race in Europe than Lovecraft was, and there’s very little direct evidence of which racist tracts Lovecraft read other than Walter Benjamin Smith’s The Color Line (mentioned in a poem he dedicated to Smith. He also owned the book Immigrant Races in North America by Peter Roberts, which is primarily taxonomic and informational rather than polemical). However, it is clear from Lovecraft’s letters that he and Grant were drawing from the same well.

Because Grant was mostly unoriginal in his concepts and also highly influential through his popularization of those concepts, it is impossible to say that echoes of Grant in Lovecraft are evidence of direct influence. Lovecraft read about the work of some contemporary anthropologists and biologists, and many of the people he drew his ideas from were people Grant had read or who, in many cases, provided direct consultation to him. Chronicling the changes Grant made for the 1918 edition of Passing of the Great Race, Spiro writes:

He numbered among his correspondents scores of scientists in the United States and Europe who were enthusiastic about the book and anxious that it be as accurate as possible. Scholars like John Beddoe, James Breasted, Henri Breuil, A. C. Haddon, T. Rice Holmes, Harry H. Johnston, Sir Arthur Keith, John Dyneley Prince, Sir William Ridgeway, G. Elliot Smith, William J. Sollas, H. G. F. Spurrell, and A. S. Woodward were continually updating Grant on issues of ethnographic significance, and he included their corrections in the revised document. Theodore Roosevelt also had a number of suggestions he wanted Grant to incorporate into the second edition, and he corresponded with Grant for many months about possible alterations.

A few of those names appear in Lovecraft’s letters (and in 1919 he published a memorial poem to Roosevelt).

The clearest influence of Grant’s ideas on Lovecraft may be in the use of the word Nordic. The term seems to have originated with the Russian-French anthropologist Joseph Deniker (1852-1918), who, Geoffrey G. Field writes, “referred to a race nordique as early as 1900″. Deniker had debates with William Z. Ripley, an economist and racist who taught at MIT, Columbia, and Harvard and whom Spiro identifies as a likely influence on Grant’s turn from working on conservation activities to working to promote eugenics. Ripley’s 1899 book The Races of Europe classified Europeans into three races: Alpine, Mediterranean, and Teutonic. Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race kept the three categories, but renamed Teutonic into Nordic, perhaps the first time the term was used in this way in English, and certainly the reason the term became a popular synonym for Ripley’s “Teutonic” and Gobineau’s “Aryan”. Lovecraft used the terms “Teutonic” and “Aryan” throughout his life, but “Nordic” became a favorite word of praise from the early 1920s onward, probably for a similar reason to Grant’s even fuller use of it in the 1918 second edition of his book: the U.S. entered the World War in 1917, Germany was the enemy, and any praise of “Teutonic” qualities seemed in bad taste.

It doesn’t much matter whether Grant himself directly influenced Lovecraft. Madison Grant and H.P. Lovecraft bathed in the same swamp.

Terror's Embodiment

I keep returning to eugenics and horror fiction because eugenics is a type of horror fiction. Further, eugenics is a fiction that has too often placed into stories premises that we ought not let trap us. Too often the fears that propelled eugenics have been the thing on the doorstep of weird tales.

The work of fear — how fear is created, stoked, spread; what is feared and who is fearing; the profits and power fear provides — is particularly important in relationship to ideas of race, especially in the United States. In her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Christina Sharpe writes that “in much of what passes for public discourse about terror we, Black people, become the carriers of terror, terror’s embodiment, and not the primary objects of terror’s multiple enactments; the ground of terror’s possibility globally.”

It is quite a feat to place a burden of fear not just onto otherness but onto the very beings most terrorized by the oppressor’s power. Those who should feel the most right to be afraid are discursively robbed of that right by the oppressors who take it for themselves.

Any white person who wants to talk about horror as something abstract, fanciful, even fun should be required to read something like what C.L.R. James writes in The Black Jacobins about the punishments committed on slaves:

Whipping was interrupted in order to pass a piece of hot wood on the buttocks of the victim; salt, pepper, citron, cinders, aloes, and hot ashes were poured on the bleeding wounds. Mutilations were common, limbs, ears, and sometimes the private parts, to deprive them of the pleasures which they could indulge in without expense. Their masters poured burning wax on their arms and hands and shoulders, emptied the boiling cane sugar over their heads, burned them alive, roasted them on slow fires, filled them with gunpowder and blew them up with a watch; buried them up to the neck and smeared their heads with sugar that the flies might devour them; fastened them near to nests of ants or wasps; made them eat their excrement, drink their urine, and lick the saliva of other slaves. One colonist was known in moments of anger to throw himself on his slaves and stick his teeth into their flesh.

Horror is not abstract, it is not fanciful, it is not fun. Horror stains every thread of history, every line of ancestry, every shadow of heredity. Which is why we ought to tell its stories. The story of the human is a horror story.

Let us not forget horror’s seriousness, let us not pretend that our eldritch imaginings are worse than what people do to each other every day.

C.L.R. James published the first edition of The Black Jacobins in 1938, the year after H.P. Lovecraft’s and Madison Grant’s deaths. Lovecraft and Grant celebrated the great Nordic men who owned the companies that enslaved and tortured people, and, through their various fantasies, they stoked their own and other white people’s fears that these enslaved and tortured people would pollute the pure blood of the Great Race.

Meanwhile, C.L.R. James and every other subaltern soul understood from childhood that it is the Great Race that ought to be feared, the Great Race that terrorizes the world.

Decline and Metamorphosis

Jonathan Spiro says that with the hindsight of history “we can see that 1924 was the high point of scientific racism in the United States.” It was the year of various federal and state laws restricting immigration, outlawing “race-mixing”, and promoting sterilization; it was a year when many of Madison Grant’s acolytes published books; a year of soaring membership in clubs devoted to heredity and eugenics; it was a year when Fitter Families contests were all the rage, college courses on eugenics proliferated, and the American Museum of Natural History “created dioramas to educate the public about the Osborn-Grant view of race and evolution”. It was also the year “The Rats in the Walls” was published.

Over the next ten years, though, the reputation of eugenic science diminished. One reason was the rise of Franz Boas and the discipline of cultural anthropology. In a December 1930 letter to James Morton, who was still trying to get Lovecraft to see that his opinions were both unscientific and bigotted, Lovecraft mocked an article Morton had sent him by proclaiming, amid much unhinged ranting, “Today it is a work of amazing naiveté to drag out poor old Prof. Boas!” But his feelings were complicated. In March 1931, he wrote to Morton, in language I will not censor because it ought to be known:

About Boas—I did not mean to belittle him unduly, though it did seem to me that he allowed social sentiments to interfere with his impersonality of deduction. What I was really laughing at was not Boas himself—whom I freely gave a place among the first-rate anthropologists—but the naive way in which all nigger-lovers turn to him first of all when trying to scrape up a background of scientific support. He is the only first rate living anthropologist to overlook the obvious primitiveness of the negro & the australoid, hence the equalitarian Utopians have to play him up for all he’s worth & forget the great bulk of outstanding European opinion—Boule, G. Elliot Smith, Sir Arthur Keith, &c. But anyway, I read of Boas’ career with great interest, & am glad that his lifetime of close & diligent research hath been rewarded by the Presidency of the A. A. A. S.

This letter was written exactly at the moment when Boas and cultural anthropology solidified their dominance over the Grantian approach. Spiro writes that “by the beginning of the 1930s the culture idea was becoming the reigning paradigm in American social science. By that time, there was nary a Grantian to be found at the National Research Council … [In August 1932], the New York Times pronounced that ‘Nordicism’ was a ‘discredited doctrine’” (p. 326). This didn’t stop Grant from publishing his second major book, The Conquest of a Continent (about North America), in 1933, but though Max Perkins called it “very impressive and important”, and no less a writer than Aldous Huxley (whose Brave New World had appeared the year before) gave it a good review in the New York American, most reviews were strongly negative, many comparing the book’s ideas to Hitler’s. By the time the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1941, only about 3,000 copies had ever sold, and during the war, Scribner’s melted down the plates.

In addition to the rise of Boas and cultural anthropology, Spiro identifies ten other reasons for the decline of Grant and his intellectual brethren:

Too much success. Immigration was severely restricted, most Americans assumed the “threat” was over.

The Great Migration. Grant, unsurprisingly, called the movement of hundreds of thousands (eventually, millions) of African Americans an “invasion of the north”. Certainly, this movement fueled lots of racism, but it also had another effect — people succeeding with new opportunities for education and employment showed some elite white northerners that their ideas of immutable traits and degeneracy were racist fantasies.

Jewish success. Similarly, Jewish people were succeeding in all sorts of different ways throughout American society. This brought the sadly predictable conspiracy-thinking about the Jewish takeover of the economy/country/world/universe/whatever, but it also made it impossible for even the most ideological people to say that Jews were incapable of great achievement.

Sociology. The field of sociology quickly moved away from biological determinism, and as the field gained prominence among intellectuals, its ideas spread.

Psychology. Some influential psychologists who had been enthusiastic supporters of eugenics found their positions difficult to sustain as the evidence mounted against them. In 1930, Carl Brigham (famed inventor of the SAT test) refuted his older views in the pages of the Psychological Review. Those views had been pillars of the eugenics movement.

Genetics. To their credit, when some scientists who had enthusiastically supported eugenics saw that the quickly-developing evidence in the field of genetics did not support their ideas, they changed their ideas. Grant, Davenport, and their minions did not, perhaps because their own identities were so deeply entwined with the idea of their genetic and racial superiority. But the field of genetics soon showed there is no such thing as a “pure race”, traits do not pass from one individual to another in the way eugenics assumed, etc. What developments in genetics showed was that the eugenic idea was not only destructive and xenophobic, but also a vast simplification of the amazing complexity of life and biology. Real scientists thrilled at this knowledge.

The Great Depression. It is easy to believe in eugenics when the idea supports your own sense of superiority. The concept became much less popular when eugenicists insisted on applying it to ordinary white Americans who were suffering in the economic collapse.

Assimilation. By the 1930s, ideas of separate races for people from around the world seemed less and less real. Generations of Italian-Americans, Irish-American, Polish-Americans, Greek-Americans, etc. had made their way in society, and the idea of “whiteness” had expanded to include many of them. Race revealed its social construction.

The Nazis. The reputation of eugenics was low at the end of the 1930s, and then, when images of the liberated concentration campus were shared throughout the country, previously-lauded concepts like sterilization and euthenasia gained a new association with horror. The Nuremburg Trials figuratively put the eugenicists in the dock with the Nazis. The new face of eugenics was not just Hitler, but Joseph Mengele. As Spiro says, “The irony is that by putting Madison Grant’s theories into practice, the Nazis discredited those theories forever.”

The Torch Was Not Passed. The Big Four of eugenics (Grant, Davenport, Osborn, and Laughlin) all died in the 1930s. Younger intellectuals and scientists had no interest in their ideas, leaving the corpse of their racism to be picked over only by the lunatic fringe. General concepts from eugenics have held on to the present day, but the details, prescriptions, and overall structure diminished in popularity.

And Lovecraft?

I can’t help but wonder if “The Shadow Out of Time”, written in 1934-1935, makes sly reference to Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race. The Great Race, Lovecraft reveals, is not Nordic — it is not even human. The Great Race is Yith.

(It is interesting, too, that Lovecraft makes the narrator, Nathaniel Peaslee, a professor of political economy rather than an archaeologist or anthropologist — this links him disciplinarily to William Z. Ripley, an economist who was prominent enough in anthropological circles of the day to likely have at least been a familiar name to Lovecraft. Ripley was less vociferous than either Grant or Lovecraft, less given to doomsaying, but no less committed to the idea of degeneration, as a 1908 Atlantic Monthly article he penned about immigration shows: “What chance is there that, out of this forcible dislocation and abnormal intermixture of all the peoples of the civilized world, there may emerge a physical type tending to revert to an ancestral one, older than any of the present European varieties? The law seems to be well supported elsewhere, that crossing between highly evolved varieties or types tend to bring about reversion to the original stock.” For more on Ripley, and much else relevant here, see The Rise and Fall of the Caucasian Race: A Political History of Racial Identity by Bruce Baum.)

In “The Shadow Out of Time”, Nathaniel Peaslee chronicles the history of humans, but his chronicle doesn’t get a very exalted place in the immense archive where beings’ histories are kept: “My own history was assigned a specific place in the vaults of the lowest or vertebrate level—the section devoted to the culture of mankind and of the furry and reptilian races immediately preceding it in terrestrial dominance.” It is as if Lovecraft, writing ten years after the apex of eugenics in the U.S., saw the lone and level sands of Grant’s (and his own) hubris drifting away.

Part Three

Researchers who were recently writing about political economy, witchcraft, ethnicity, religion, or the state are suddenly rethinking these topics through interspecies relations. I’m hoping this is not just an attempt to jump on a trend but rather a realization that life on earth is changing. As I see it, livability as we have known it has been threatened, and all kinds of human — and more-than-human — endeavors will experience the consequences. Of course, other anthropologists are arguing that multispecies anthropology is a distraction from serious critical inquiry. But I think these critics are not paying attention to changes in what we all will have to do to stay alive, as well as changes in the academy.

—Anna Tsing, interview, Suomen Antropologi, 2017

The Tragedy of the Past Isn't Past

It surprises me that there have not been more studies linking H.P. Lovecraft and William Faulkner. On the one hand, it is not surprising — Faulkner and Lovecraft were from radically different milieux, one is a Nobel Prize-winning paragon of High Modernist Literature while the other is a paragon of the pulps, one declared “I have never tasted intoxicating liquor, and never intend to” while the other was a notorious alcoholic, and for all Faulkner’s pretenses of being a simple southern farmer of moderate views (especially in the last 20 years of his life) his understanding of race and history was significantly more nuanced than Lovecraft’s.

And yet. Both writers created their own worlds while also being committed to a small region; both were, in their own ways, fascinated by language and determined to render English into something rich and strange; both had an obsession not just with history but with what history does to the present; both had a certain Gothic sensibility and an interest in the mythic; and both wrote about the fear of impure ancestry and degeneracy. And though Faulkner had a less narrow and hate-filled view of race than Lovecraft, and perhaps valued women (slightly) more than Lovecraft did (Judith Sensibar’s Faulkner and Love: The Women Who Shaped His LIfe is a powerful study of that), the deepest limitations of both their bodies of work are limitations of race and gender.

(There is even some trivia of direct overlap: We know that Lovecraft read Faulkner’s short story “A Rose for Emily” — it was included alongside Lovecraft’s “The Music of Eric Zann” in the 1931 anthology Creeps by Night edited by Dashiell Hammett. In a February 1932 letter to J. Vernon Shea, Lovecraft said, “I don’t underestimate Faulkner. A Rose for Emily is a great story, & all I said about it was that it is not weird. It belongs to a different genre, & brings a shudder of repulsion & physical horror rather than one of cosmic wonder.” I am unaware of any evidence that Faulkner read Lovecraft.)

Heritage provides horror in Faulkner, and there is at least as much anxiety about blood and miscegenation in Faulkner as in Lovecraft, but the horror and anxiety are rendered utterly differently. Faulkner had as deep a sense of tragedy as any American writer of the 20th Century (Toni Morrison, who wrote a master’s thesis on Faulkner and Woolf, is perhaps his greatest rival in tragic sensibility), and the horror in Faulkner’s best work is always accompanied by a sense of melancholy, a sense of loss and waste.

Perhaps the difference between the view of heritage in Faulkner’s work and in Lovecraft’s is that where Lovecraft yearns for the lost past and its aristocratic germ plasm, Faulkner sees the past as a curse and ancestry as, from the beginning, infused with rot.

For many characters in Faulkner, the curse of history brings madness and downfall, as it does for Delapore in “The Rats in the Walls”. Lovecraft’s story could fruitfully be placed in comparison with Faulkner’s greatest novel, Absalom, Absalom!, because despite Faulkner’s infinitely more complex text, both works evoke heritage and place as horror, and both culminate in types of madness. Absalom, Absalom! even ends with Quentin Compson up in Lovecraft’s New England for college, where his Canadian friend Shreve offers a vision of the passing of the race: “Of course it wont quite be in our time and of course as they spread toward the poles they will bleach out again like the rabbits and the birds do, so they wont show up so sharp against the snow. But it will still be Jim Bond; and so in a few thousand years, I who regard you will also have sprung from the loins of African kings.” This vision has certain affinities with the vision in Lovecraft’s short novel At the Mountains of Madness (like Absalom, published in 1936) of the decline of the Old Ones and the rise of the shoggoths. Timothy Murphy lays it out clearly: Lovecraft’s “plot culminates in the revelation that in the distant past the shoggoths rose up to overthrow and exterminate their Old One masters”. The shoggoths’ “combination of threatening mutability, unsettling shapelessness, and precarious enslavement has led some critics, such as China Miéville, to see in the shoggoths an image of the rising multiethnic proletariat”. In Absalom, Jim Bond doesn’t rise up, though; he simply, in Faulkner’s word, endures. But the fear of one heritage wiping out another is clear in Shreve’s story, and it is a fear flavored with further prejudice from knowledge that Jim Bond is mentally challenged, making him an exemplary prototype for any moral panic about degeneracy.

After speculating about the future, Shreve goes right into the famous final question: “Now I want you to tell me just one thing more. Why do you hate the South?” To which Quentin issues his final, repeated, anguished cry in “the cold air, the iron New England dark”: “I dont hate it! I dont hate it!” After finishing the novel, do we believe him? The novel also leaves us to ask if we, ourselves, do not hate the ancestry that Quentin inherited. And what might we do with such knowledge of our feelings? From The Sound and the Fury we know that Quentin drowned himself in the Charles River, choosing his own end in the land of the Mayflower Pilgrims. It’s right around this same time that Clytie — daughter of Thomas Sutpen and an enslaved woman, family caretaker, keeper of secrets — burns down the haunted wreck of a plantation house so important to Absalom, Absalom!, old Sutpen’s Hundred, not necessarily ending the curse of history, but at least letting some ghosts go free.

Despite Clytie’s great action, we must acknowledge that the question of the tragedy of history is, in Faulkner’s work, a question for white people. Édouard Glissant makes this point in Faulkner, Mississippi (a book of meditation, rumination, mystery): history is full of horror for all sorts of people, but, he writes, “it is only to White people that the question — the nagging question of original responsibility — is addressed”. The portrayal of white history in Faulkner’s oeuvre is far from glorious, but it nonetheless is a portrayal of change over time (not necessarily better, but it is change). In portraying genocide and slavery as original sins, Faulkner makes the story of history the story of white people. Glissant notes that in his work, Faulkner’s “descriptions of Blacks cannot be other than immobile: Blacks are permanency itself. The rural life that confines and signifies them is the site of the absolute. … In this hidden inquiry into origins (of the county and its maledictions), to which his works always give (or rather propose) answers that are forever postponed (into the infinity of Time and Death), Blacks are and represent the unsurpassable point of reference, those who remain and who assume.” This removes people from history, removes them from action, renders them into objects and abstractions. It denies not only humanity but community.

In Darwin and Faulkner’s Novels: Evolution and Southern Fiction, Michael Wainwright offers readings of Faulkner’s books that often are at odds with Glissant’s readings regarding Faulkner’s presentation of race and heritage, yet there is overlap in the overall ideas both writers present — ideas about Faulkner’s need (because of his positionality) to render his most subversive tendencies via the background of the text, and the value (and difficulty) of his polyphonic, carnivalesque narratives. Of Light in August, Wainwright says: “Faulkner knew that his criticism of an inveterate discourse had to be subtle. Otherwise, reactionaries would reject his novel as a liberal tract. A narrator in keeping with the social and racial hierarchy of the South enables Faulkner to achieve his aim.” Of Faulkner’s art generally he writes that we “must have a sense, a common sense of morality based on the recognition of alterity, alterity with others and alterity with one’s other selves as time elapses” and argues that this “state to come, a struggle without solution” is central to Faulkner’s ideology, an ideology that is comfortable with aporia and agonistic struggle, the unresolved and irresolveable. Stories can help bring this ideology to life in our heads, moving the abstract work of morality toward concrete situations. Glissant says that there is in Faulkner’s work “a deferral of the absolutes of identity, and a vertigo of the word…” The narration is perhaps the most important feature of Faulkner’s vision, and even the third-person narratives have a strong sense of being stories told, a deep particularity and concreteness. “The word in Faulkner,” Glissant says, “is constantly caught up in concrete realities, in everyday speech, in animal or human forms, in the harshness or sweetness of plant life, in a sort of common pleasure in brute existence, if not also in a jovial or angered vulgarity of people and things … all of which mask the intentions of their words. … The oral techniques of accumulation, repetition, and circularity combine to undo the vision of reality and truth as singular, introducing the multiple, the uncertain, and the relative instead.”

The multiple, the uncertain, and the relative. The past as story told now. Which story will we tell?

If we are telling stories, we are then in the realm of imagination. The limits of our imagination are the limits of our worlds.

Consider, for instance, The Unvanquished, a collection of closely linked stories that were originally published in mass market (“slick”) magazines between 1934 and 1936, then revised, with one new story added, for the book. (With his magazine stories, Faulkner wrote what he thought people wanted to read, because usually he needed quick money from selling those stories. His books he took seriously.) The Unvanquished has sometimes been disparaged as an embarrassing collection of nostalgic tales contributing to a Lost Cause ideology; that’s easier said of the original magazine stories than the book, though. The final chapter, the one written for the book, offers an often heartbreaking perspective that recontextualizes everything before it, showing that this is a story about the ways history, society, and patriarchy warp innocence and goodness toward ideologies of superiority and violence. The surface of the book tells a story of the Sartoris family, but the heart of the book is the relationship between Bayard and Ringo, and the ways a sick society infects that relationship, ultimately destroying it. As Michael Gorra points out in The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War, the tragedy at the end of The Unvanquished is both of the characters and of Faulkner, people born into a world where a future for Bayard and Ringo as old friends is unimaginable:

Their intimacy belongs only to childhood, to a time that can, however briefly, sustain the illusion of an undifferentiated equality. It cannot extend to an adult life in the Redeemed South that is coming up around them, in which the gains of Reconstruction will be canceled by Jim Crow. In that world, Ringo could live only as Bayard’s client, only as what Zora Neale Hurston would later call a “pet Negro.” And Faulkner simply didn’t want to see him that way. He didn’t want to show us what Ringo might be at thirty or forty and with a family of his own; what he might become if he ever left the Sartoris land, and how diminished he would be if he didn’t. He couldn’t imagine an adult life for him. Or rather he chose not to, having first imagined that intrepid intelligent adolescent. He never took the character further, and after finishing The Unvanquished he didn’t go back to the adult Bayard either, not as anything more than a passing reference; never returned to a life in which he would have to explain an absence.

What can be imagined?

What do we choose to imagine?

Here, we have reached a pivotal moment in our journey.

Fear and Love

The fear we see in Madison Grant’s writings, in Lovecraft’s narrators, in Faulkner’s white characters is a fear of communal humanity. It is the assertion of heritage over community, a simultaneous veneration of and anxiety for family lineage. We can see it as a fear of symbiosis, and note the tragedy that both Faulkner and Lovecraft at least intuited: the purity so desired by racists and eugenicists is anathema to nature. “The fusion of genomes in symbioses,” Donna Haraway writes in Staying with the Trouble, “followed by natural selection — with a very modest role for mutation as a motor of system level change — leads to increasingly complex levels of good-enough quasi-individuality to get through the day, or the aeon” (60). Those complex levels are the healthy ones, not ever-more-etiolated family trees.

Faulkner knew this. It is infused through the deep structure of his best work. Lovecraft’s stories, too, are aware of this truth, regardless of what their author himself consciously thought. Nathaniel Peaslee in “The Shadow Out of Time” speaks for many of Lovecraft’s narrators when he declares, “I shivered at the mysteries the past may conceal, and trembled at the menaces the future may bring forth.” This is these characters’ tragedy, their terror that their blood may be filled with rot and sin. The characters may be tormented, but the stories present more ambivalence. Even the best of the early stories demonstrate this. Joel Lane writes of “The Rats in the Walls” that the “de la Poer family exemplifies the features that Lovecraft himself considered true signs of class: they are English aristocrats who became slave-owners in the USA and fought on the Confederate side. That they are revealed as cannibals in thrall to inhuman evil is a sign of Lovecraft’s ambivalence towards the family whose colonial credentials he upheld as proving him to be a true ‘gentleman’.”

Lane recognizes that all the folderol about “cosmic horror” distracts us from the fact that an important conflict at the heart of Lovecraft’s work is ”the conflict between love and fear of the family.” It is also a conflict between love and fear of oneself, not only one’s idea of a personality, but one’s own body and biology (which is also about inheritance and the family). There is throughout Lovecraft’s fiction a yearning for bodies to be healthy and stable and noble (Nordic!) coupled with a realization that bodies, like everything else, are impure and ever-changing.

Joel Lane prompts us to ask why an idea of humanity having no influence on the universe should matter to us:

A distant planet is unresponsive to human needs, but so is a snowflake or a carbon atom. Lovecraft’s “mythos” stories always contain thematic threads related to human society, communities, families, and individuals — and this is not incidental, it is integral to their meaning and impact. These stories are not about “the cosmos”, they are about the invasion and erasure of the human.

It does not matter to the universe writ large what any human thinks or does, or even what the whole species thinks or does. Our planet is but one among countless others. Even as a species, our time is short; as individuals, our lives are brief candles. (Our plastic and our nuclear waste will outlive us all.) But within the flicker of our lives, how we live in our communities, how we relate to each other, does matter. It matters to us. And not just us as humans, but us as beings together with all other beings we share the planet with, interconnected in this moment of time.

We need, Donna Haraway says, to “exercise leadership in imagination, theory, and action to unravel the ties of both genealogy and kin, kin and species” (102). Kin is a key word for her, a way to escape the tyranny of hierarchy and the claustrophobic confines of family: “Kin making is making persons, not necessarily as individuals or as humans. … I think that the stretch and recomposition of kin are allowed by the fact that all earthlings are kin in the deepest sense, and it is past time to practice better care of kinds-as-assemblages (not species one at a time). Kin is an assembling sort of word” (103). Our task is now to recognize the assemblages of which we are a part.

Staying with the Ancestor Trouble

Haraway’s concept of kin might be one way to wash some of the residue of eugenics out of contemporary discussions of genes, particularly in popular culture and politics. Kin not as family or the people we see ourselves bound to by race or identity, but kin as the beings assembling with us. Narrow ideas of ancestry or heritage will only do us harm.

In her recent book Ancestor Trouble, Maud Newton writes:

Twentieth-century proponents of eugenics advanced it as a remedy for a wide variety of perceived heritable shortcomings, including lack of intelligence, as defined by the eugenicists themselves. These impulses are very much with us now. Donald J. Trump, former president of the United States, credited “good genes” for his success, intelligence, and health, and the orange glow of his skin. “I always said winning is somewhat, maybe, innate,” he said in an interview. “You know, you have the winning gene.” Elsewhere, he observed that when you “connect two racehorses, you usually get a fast horse.” And at a rally in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election, he explicitly endorsed “the racehorse theory.” Michael D’Antonio, author of a biography of Trump, contended in a PBS documentary that Trump believes “there are superior people and that if you put together the genes of a superior woman and a superior man, you get superior offspring.”

Those ideas are no different from the ideas of eugenicists, but I would also bet lots of money that those ideas are today how many people think genes and heredity work. Newton even quotes the famed scientist and atheist Richard Dawkins, author of The Selfish Gene, as saying that “sixty years after Hitler’s death, we might at least venture to ask what the moral difference is between breeding for musical ability and forcing a child to take music lessons.” She adds: “Three seconds of searching YouTube will unearth much of this same sort of thinking, some of it propagated by violent white supremacists.”

The rise of genomics, epigenetics, and related fields has led to thrilling discoveries, but the progress of science also (especially within capitalism) poses complex ethical quandaries. “With studies into loaded subjects like anxiety,” Newton writes, “we could wind up right back at a place where a woman’s behavior or state of mind during her pregnancy could be blamed for her child’s strawberry birthmark, or someone’s own traumatic experience could be considered to contaminate them for life. You were bullied at school? Sorry, you’re sullied goods. I can’t procreate with you.” And then there’s the way genetic information is being used by police, by governments, and by global corporations. Newton points to the artwork of Heather Dewey-Hagborg which has used “Forensic DNA Phenotyping” (FDP) to show the ways genetic surveillance endeavors “reflect the assumptions and motivations of their designers” — for instance, groups such as Parabon Nanonlabs, who in 2015 collected litter in Hong Kong and used the genetic material on the litter to create portraits of “litterbugs” and then publicize those portraits on posters and in videos.

Newton points out that the genograms so common among genealogists today bear a strong resemblance to the charts used by the Eugenics Record Office, and can be used for similar purposes. She notes that Garrard Conley’s memoir Boy Erased describes their use by the “ex-gay” movement. “Among many horrible things,” Newton says, “including watching his writings be destroyed in front of him, Conley was required to create a genogram that according to the program leaders would show how various tendencies in earlier generations were antecedents to his queerness.”

Ancestor Trouble is about coming to terms with ancestry and history, about embracing the complications, facing the challenges, finding joy in a kinship partly inherited, partly chosen, partly imagined. A kinship not only of family (chosen or not), but also of place and nature. “Historically,” Newton writes, “the connection between humans and the land was obvious. People were of the land, nourished by it and buried in it, and thus nourished it in return. The earth was kin.” Many people are now alienated from that once-ubiquitous sense of place and belonging. (Even our dead bodies have trouble breaking down in the soil, returning to the earth.) This sense of kinship with the biology supporting our existence is what Donna Haraway argues for, a kinship of people and planet, of humans and other animals, of microbes and their biome-bodies.

It is that sort of expansive kinship that terrified eugenicists and terrified Lovecraft’s narrators, an expansive kinship that Faulkner seems often to have yearned for yet lived in a world where it was unimaginable.

Lovecraft, too, yearned, though he never would have admitted it. The yearning screams from his stories.

In Lovecraft’s late stories especially, this kinship — not just the yearning, but the kinship itself — becomes more available to us, the readers, as the narrators’ sense of horror seems less and less justified by the text. We ought to be able to recognize the extraordinary range of life and experience the vision of history in “The Shadow Out of Time”, for instance, offers. Lovecraft’s narrator is so bedazzled by the idea of decline and fall that he almost doesn’t appreciate what he has seen, but he gives the evidence to us, and even if he can’t stop clinging to his idea of blood and self, he ultimately admits to having experienced “dizzying marvels”:

There was a mind from the planet we know as Venus, which would live incalculable epochs to come, and one from an outer moon of Jupiter six million years in the past. Of earthly minds there were some from the winged, star-headed, half-vegetable race of palaeogean Antarctica; one from the reptile people of fabled Valusia; three from the furry pre-human Hyperborean worshippers of Tsathoggua; one from the wholly abominable Tcho-Tchos; two from the arachnid denizens of earth’s last age; five from the hardy coleopterous species immediately following mankind, to which the Great Race was some day to transfer its keenest minds en masse in the face of horrible peril; and several from different branches of humanity. I talked with the mind of Yiang-Li, a philosopher from the cruel empire of Tsan-Chan, which is to come in 5,000 A.D.; with that of a general of the greatheaded brown people who held South Africa in 50,000 B.C.; with that of a twelfth-century Florentine monk named Bartolomeo Corsi; with that of a king of Lomar who had ruled that terrible polar land one hundred thousand years before the squat, yellow Inutos came from the west to engulf it. I talked with the mind of Nug-Soth, a magician of the dark conquerors of A.D. 16,000; with that of a Roman named Titus Sempronius Blaesus, who had been a quaestor in Sulla’s time; with that of Khephnes, an Egyptian of the 14th Dynasty, who told me the hideous secret of Nyarlathotep; with that of a priest of Atlantis’ middle kingdom; with that of a Suffolk gentleman of Cromwell’s day, James Woodville; with that of a court astronomer of pre-Inca Peru; with that of the Australian physicist Nevil Kingston-Brown, who will die in A.D. 2518; with that of an archimage of vanished Yhe in the Pacific; with that of Theodotides, a Greco-Bactrian official of 200 B.C.; with that of an aged Frenchman of Louis XIII’s time named Pierre-Louis Montagny; with that of Crom-Ya, a Cimmerian chieftain of 15,000 B.C.; and with so many others that my brain cannot hold the shocking secrets and dizzying marvels I learned from them.

In Ancestor Trouble, Maud Newton reveals that she is a descendant of Mary Bliss Parsons, “the Witch of Northampton”. The discussion of Parsons opens a section of the book titled “Spirituality”, though in many ways I thought it might also be titled “Occult” or “Imagination”. (What is spirituality if not occult imagination — that is, imagination of the hidden, the unseen, the unknown and unknowable?) Without knowing the family history, Newton’s sister moved to Northampton, Massachusetts in the 1990s. After discovering their lineage, the sisters visit their ancestors’ graves, discovering “a Parsons family monument commemorating Mary, her husband, and their descendants. Many old family headstones were no longer legible, but a marker for Mary’s eldest son, Joseph, Jr., my eighth great-grandfather, was perfectly clear, etched with a winged skull. Later we learned that my sister-in-law has ancestors in the cemetery, too.”