Late in Joel Lane’s 2003 novel The Blue Mask, a character discusses his favorite books by Jean Genet:

“I often think his scenarios are built up, not just from solitary fantasies, but from real sex. The books are a fundamental part of his love life. What he does on the page, he does in himself. That’s how he survives.” His own favourite Genet novel was Miracle of the Rose, “because it’s the most liberating. It’s about the freedom of the imagination. It makes you feel that anything is possible. Funeral Rites is beautiful, but it’s a book without hope.”

This passage resonated with me because in recent months I have been thinking about how we not only educate our imaginations, but how we feed them, how we sustain them, and, perhaps most importantly, how we heal them after (and despite) loss and suffering.

Creative people respond to suffering and loss in various ways, but my experience is that I cannot write much in the midst of the worst of things, and sometimes the long effect of grief or pain destroys the ability to create for months or even years at a time. After my mother’s death in November 2018, I did not finish a new short story until June 2019. That story was “A Liberation”, first published by Conjunctions and reprinted in The Last Vanishing Man. I tried writing other things, but nothing came together. My oldest, dearest friend in the writing world, Katherine Min, herself died in March 2019, and the story is dedicated to her, but it could also have been dedicated to my mother. The whole story was an attempt to help myself get back to being able to imagine anything other than loss.

Grief, suffering, and trauma may narrow our visions, hollow out dreams, render words and images empty. There’s a ghostly, haunted quality to life because life itself feels like the ghost. Some people are able to create art in the midst of this, using their creativity to find their way back into the world, but that’s not been true for me, generally. For me, the imagination has to recover first.

That recovery can feel like a large change. I don’t know if readers notice a distinct difference between “A Liberation” and the stories that came before it (probably not), but for me it’s a key juncture, a story reaching toward a different sense of possibility than what came before, a story written from a different world than the world that birthed my earlier stories.

Feeling the imagination has been made into a wasteland by suffering is different from a more general sense of writer’s block. There are lots of reasons why it can be hard to write, hard to get narrative forms to find shape on the page, hard to keep going when it feels like an endless slog. That’s one set of feelings, the feelings of relatively ordinary writer’s block. But the imagination has other ways of falling apart, and suffering undoes it by erasing a sense of possibility, hollowing out any vision of futures and alternatives, dessicating anything but the most immediate, numbing sense of the world itself as loss.

*

“What would life be like, he wondered, if all the parts of ourselves could talk to each other? Bones, skin, memory, need, hope?”

—Joel Lane, The Blue Mask

*

How do we heal when the imagination has been so assaulted, so ennervated?

Certainly, time helps. But for myself, I know i have had to do some deliberate work to return to imagining. Grief and suffering are demons that tell us there is no point to trying, that everything is now as it will always be, that numbness and pain are the only options. This feels terribly true for a while, incontrovertible, and that feeling likely can’t be overcome quickly, but step by step we can plant seeds of dreaming … and eventually new worlds bloom.

Often for myself it has been ancient Chinese and Japanese poetry that helped me find my way back to imagining. The precision and concision of the Chinese mountain poets or the Japanese haiku poets helps me ground my sense of language and imagery. Visual art is also powerful — I am lucky to have a good collection of art books, collected since I was in high school (when I was 18, I carried a couple heavy books all through Paris because they were on sale at the Musée d’Orsay!), and when I am at a point of weakened imagining, I just skim through books, seeking out colors and shapes, images, ideas. I have very little visual imagination even at the best of times, and something about having to stretch my memory and senses visually provides more effect than spending time with words and music, art forms that fit within myself more easily (I am obviously a word person, but also very aural, so music is a constant comfort).

I expect every creative person has their own unique route to a reinvigorated imagination, but I for most of us it probably comes down to some sort of grounding (for me via the efficient concreteness of certain types of poetry) and stretching ourselves (for me via visual imagination).

*

“Personal loss is an important literary theme and one that I return to quite often, but it can get a bit monotonous if that’s all you’re talking about. The challenge is to understand how people keep going, how they survive – emotionally as well as physically. Life is a struggle and in the end you lose everything – that’s a given and there’s no point just saying it, you have to show what it brings out of people.”

—Joel Lane, March 2013

*

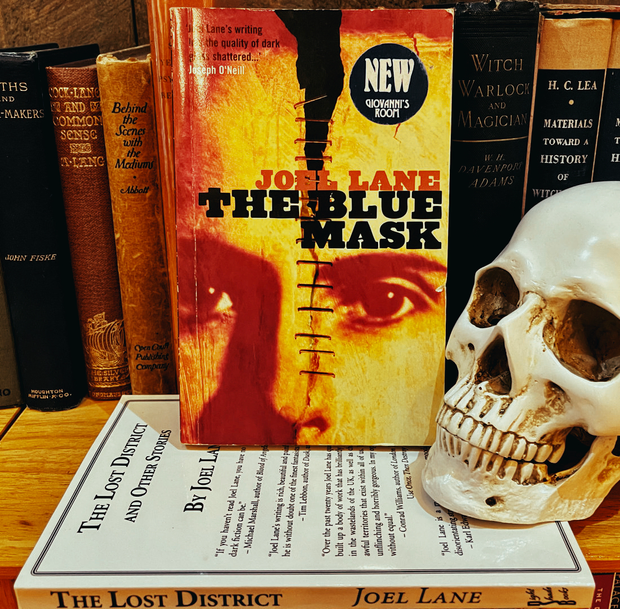

In preparation for a panel discussion at Necronomicon in August about the work of Joel Lane, I’ve been rereading old favorites and filling in gaps in my knowledge of Lane’s extraordinary body of work. He was important as a writer of horror short fiction, but that (well deserved) reputation obscures the fact that he was a writer whose sensibility carried across various genres, a fact that became especially clear to me when I read The Blue Mask, which is not really a horror novel in any genre sense, but it is a powerful and sometimes profound exploration of violence, suffering, healing, and imagination.

(The Blue Mask has never been published in the U.S., but the recent Influx Press edition is easily available via online retailers — I recommend Blackwells for a good price and free U.S. shipping.)

The novel tells the story of Neil, a queer PhD student working on a dissertation on fascism, who one night after a minor fight with his boyfriend ends up going to a bar and picking up a young man who then attacks him fiercely, disfiguring his face terribly. The majority of the book is about Neil working his way back to the world after being both violently attacked and having his face destroyed.

It’s also very much a story set in a historical moment and a specific place: the late 1990s; Birmingham, England. Lane was always a master of evoking aspects of industrial and post-industrial England’s urban environment, particularly Birmingham, and The Blue Mask contains some real tour-de-force descriptions, descriptions that don’t simply create an image but summon feelings, sounds, and shapes that turn landscape into mindscape (and vice versa).

For some readers, the frequent political discussions between the characters and the constant citing of songs and bands may feel irrelevant and even annoying. I felt this myself with some of the songs, especially of bands I’m not familiar with, but the technique really does evoke a specific time. The political discussions ultimately serve a valuable purpose, too, as the novel moves its way toward ideas of the personal and political intertwining. Part of what Neil ultimately has to rebuild is his sense of political imagination, especially his sense of his own relationship to fascism and its violent dreams of assault and extermination.

Neil, wounded and traumatized, must find some way to make his hurt and his desire active rather than passive (he needs to do something), and then productive rather than destructive. He finds a way toward something active after a claustrophobic moment in the catacombs of Paris: “For a moment, the past had trapped him. But now, he was coming back to the surface. And the assassin wouldn’t find him. He was the assassin.”

It’s a breathtaking moment in the context of the novel because up to that point, Neil has been sullen and wounded and stuck. Understandably. But by that point, it’s easy to begin to get annoyed with him for not taking more control of his own recovery. After the catacombs, he does.

What Neil does is, for the most part, neither healthy nor helpful, except that it’s more helpful than being passive and static. He loses a lot, create a new sort of identity for himself, tries to become something of a predator (he’s not all that good at it!), and develops a significant problem with alcohol. He’s active, but his activity is mostly destructive (mostly self-destructive, though that’s not his goal). It isn’t until the last two chapters of the novel that, with the help of both friends and strangers, he finds a more productive way to heal. And a more productive relationship to violence and hurt.

The astonishing penultimate chapter, titled “The Room Without the Light”, is the highlight of the novel for me, a chapter depicting education and imaginative healing that is not in any way comfortable or safe. Neil finds someone who can carry him into the darkest realms of his desires, and that journey is perilous, but the result is liberation. It works because it is conducted with something like love.

Joel Lane was not starry-eyed about love. But he also wasn’t unthinkingly cynical. He did not have a lot of fond things to write about families or domestic bliss, but when his characters find something like contentment, or even grace or salvation, it is thanks to some sort of love and intimacy (sometimes sexual, often not).

In a recent newsletter, Zen priest Christina Moon pointed out that the word compassion can be traced back to Latin: com- (together with) + pati (to suffer) — thus, at its most etymologically literal, compassion means to suffer with. “In modern contexts,” she writes, “we tend to understand compassion as more like having sympathy with or understanding someone else’s suffering. I like this older understanding because it forces the recognition that suffering with someone—to share in their suffering—requires strength.”

This is true, but there’s also a sense of solidarity in the etymology. It’s not about just having sympathy for somebody, or empathy, or whatever — true compassion is about bearing their suffering with them. This is a quality I notice in Joel Lane’s writings. Neil in The Blue Mask ultimately finds his way out of the darkness because he encounters real, old-school compassion. He ends up somewhat confused about love and its place in his life, but there is no question that a series of truly compassionate acts by various people (some of whom hardly knew him) led to his recovery. The extent of that recovery is left open at the end of the novel, but that he has recovered at least a bit of his purpose and humanity is not in question.

*

And someone leads the beast in on his chain

But I know you’re thinking of me ’cause it’s just about to rain

So I won’t be afraid of anything ever again

*

I don’t know how much other readers connect with The Blue Mask, but I am almost the perfect audience for it, and it is a book I will long treasure. First, I like Joel Lane’s writing generally — his sense of rhythm and his favorite sorts of imagery appeal deeply to me, even though I have never been to Birmingham and my own day to day environment is a rural one. Still, ever since reading The Lost District when Nightshade Books sent me an advance copy (I’d never heard of Joel Lane before that), something in his words’ rendering of the physical and psychological worlds resonated with my own sensibilities.

But The Blue Mask is work I connected to more deeply than anything else of his I’ve read. Of course, there’s Neil’s boyfriend’s name: Matt, a medical student who enjoys horror movies and horror stories, and is an all-round decent guy, if a bit conventional. I very much approved of my namesake in the story!

More importantly, I know something about facial grotesquerie. At the end of my time in high school and through my first years of college, I suffered a rare disorder that caused my face to swell and sometimes to break out in pretty severe and hideous acne. It got so bad that many mornings I could not open my eyes until I’d sat up for a while. My face was noticeably strange. (In an elevator one day, a random guy asked if I’d been stung by a bee.) Eventually, thanks to dermatologists at NYU Medical Center and a heavy dosage of pretty nasty medications, I got my face back. (Which is how I’ve always thought of it. I got my face back.) I can’t tell you how many little things you do to hide and protect yourself when you feel repulsive. A lot of it becomes unconscious. The Blue Mask understands this. It’s not comprehensive in its representation of someone with facial disfiguring, but it doesn’t need to be — it does what all good fiction does and activates our imaginations to understand what it is like to look significantly different enough from other people that their natural reaction is to stare and (more obnoxiously) to comment. Aside from Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face, I don’t remember reading anything other than The Blue Mask that so deeply understands such experience.

The milieu of the novel is one that also appeals to me, because though the specific setting is not one I know, the world of gay bars and nightlife in the 1990s is something I experienced, for better and worse. Pretty much everything that happens in that setting in The Blue Mask reminded me of things I saw and, in some cases, participated in. That world is pretty much gone now — certainly, it’s gone for me — but its history, good and bad, is important, worth holding onto, and The Blue Mask allows us to glimpse that, to spy for a moment on ways of living left in fewer and fewer people’s memories.

Ultimately, though, it is the journey of Neil that makes The Blue Mask a new favorite for me, because the ways that Lane structured that journey offer some hints of how to imagine love and healing in a universe of persistent doom. This is something I have been struggling with in my own imagination. I am not an optimist about the future, yet I try to be optimistic about the future of myself and the people I care about. Living hardly seems worthwhile otherwise. How might art help us with this? How might we foster ideas about love, intimacy, and maybe even hope against the certainty of suffering and apocalypse? This has long been one of my own themes, consciously and perhaps unconsciously — About That Life is directly about it — but I feel that my fiction has said all it can say about the limitations, and I’m now looking for other paths. The Blue Mask is one. It is a book about apocalypse and survival, about suffering and love, about disfigurement and healing. None of its conclusions are easy, few are traditional or expected, and the story promises no great, lasting, eternal happiness for its characters. Nonetheless, its ending is one I find light and uplifting in the best sense, almost transcendant. That’s a significant achievement.

The sad thing is that Joel Lane is not here to help us live through our days anymore. He died in his sleep in 2013, very soon after his collection Where Furnaces Burn won the World Fantasy Award. He had plans that went unfulfilled, and reading his recital of them in a 2011 interview brings me great sadness: “Longer-term projects include a book of metaphysical ghost stories, a book of more ‘extreme’ horror stories, a pamphlet of erotic poems and a supernatural horror novel set in the Black Country.”

Joel Lane is gone, but his work still shows us a way forward, a way of rebuilding our imaginations from here in the ruins.

*

“…if the truth of our lives is nothing, then the only reality is the one we bring to life. After all, our cities — our tower blocks, our bridges, our streets — are human constructs. They didn’t come from nature. Why should our dreams, desires, and fears be any different? Whatever we make in our lives — love, violence, hope, betrayal — is the only reality that won’t fall down overnight.”

—Joel Lane, The Witnesses Are Gone