In 2018, I wrote a post at The Mumpsimus about Raymond Carver, inspired by Brian Evenson’s little book about Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Soon after I published it, Google decided the post was plagiarized clickbait and removed it. I could never figure out what was causing the algorithms to determine this, nor did any of my appeals do anything. I tried to strip out the links and republish it, assuming something in the code had caused the systems to determine the post was a violation of something or other, but when I republished it, I got a stern automatic email about trying to republish forbidden content and the post was again removed by Google. It was truly bizarre. I didn’t like the post enough to want to fight about it or recreate, so I forgot about it.

Looking for something else today, I remembered the post. I still had some remnants in draft in Blogger, so was able to find the original date and link, allowing me to use the Wayback Machine to find the original version of the post.

There are some ideas and references in this piece that I want to be able to refer to in the future, so it’s important to resurrect this from Google’s bizarre, automated vendetta against it. (The formatting may be a little weird at times, because Patreon hates all cut and paste and doesn’t always display things in the way they will be published, but so it goes.)

Reading Raymond Carver Now

originally published at The Mumpsimus, 12 May 2018

Put Yourself in My Shoes

After finishing my doctoral dissertation a month ago, I found myself with free time to read whatever I wanted, a luxury that has been rare over the last five years. The only things I wanted to read were short stories. I needed to clear my mind of all the words and ideas and feelings that the nearly-500 entries in my dissertation’s bibliography mapped, the years of skimming and mining books and also reading books over and over, slowly, carefully; both exhausting practices that developed an intellectual armature I now felt weighed down by. One of the central topics of my dissertation is the novel as a form, and once I’d submitted the final draft to the university for archiving, my brain seemed to want to have nothing to do with novels for a while. (This did not surprise me, as it’s typical of what happens at the end of a big project — after working as series editor on the Best American Fantasy anthologies for three years, for instance, I didn’t read any short fiction for months, and even after returning to reading it, for at least a couple years I read vastly less than I had before.)

What sort of short fiction did I read? At first, just whatever happened to catch my eyes, various styles and genres. A potpourri. Then I found myself reading stories by men. For a while now, the significant majority of fiction I’ve read that wasn’t for school/work has been fiction by women. It wasn’t a conscious decision either way — I didn’t make a pledge to read primarily work by women, nor did I recently say to myself, “Enough with these women! Bring me men!” It was simply the way of it, and I noticed the new pattern only after I was on my fourth or fifth book. With one exception, the writers were not particularly Men’s Men, many weren’t exclusively heterosexual, few showed any great interest in traditional, patriarchal ideas of masculinity.

The exception was Raymond Carver.

Viewfinder

I hadn’t read a Raymond Carver story in at least ten years. But reading Carver was like a time traveler returning to an important personal moment: seeing the experience while also having some distance from it. When I was in my early teens, beginning to wonder how to write short stories that weren’t just whizbang sci-fi, I heard somewhere that Raymond Carver was the most important contemporary American short story writer. (I expect it was Writer’s Digest, which my parents gave me a subscription to for my birthday. I think they published a review of an anthology Carver co-edited with Tom Jenks, American Short Story Masterpieces. Eventually, that book became a training manual for me, but only after I’d sought out Carver’s own stories.) I visited the library and found Where I’m Calling From. I read some of the shorter stories in it and found them fascinating, if beguiling. How were these stories? Their endings especially perplexed me, because they didn’t feel like endings. There was something about the rhythms, though, particularly of the dialogue, that thrilled me. The longer stories mostly bored me, but the shorter ones, they were something special.

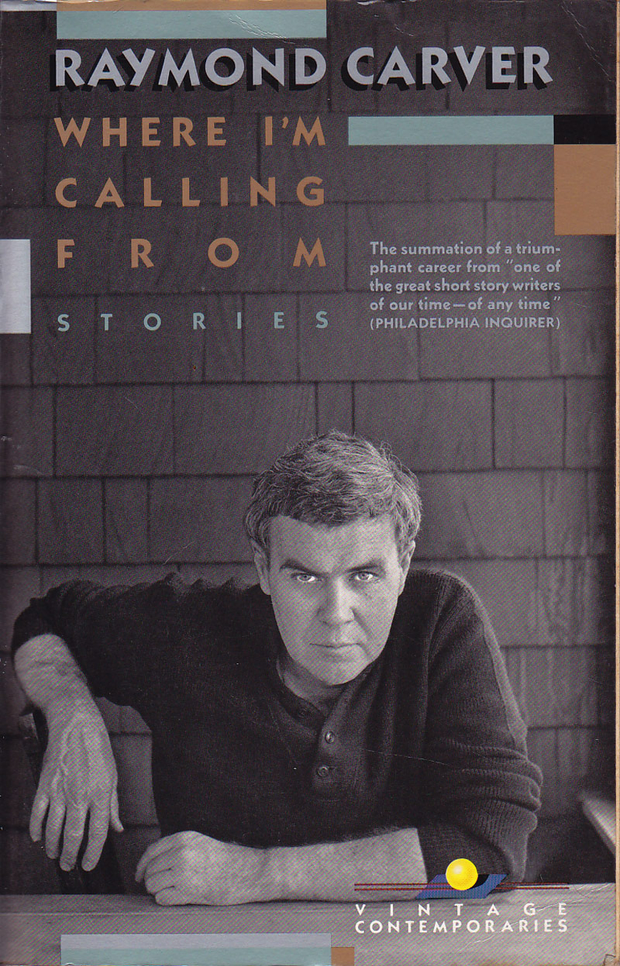

The library’s copy of Where I’m Calling From was the hardcover from Atlantic Monthly Press. At a bookstore, I saw the Vintage Contemporaries paperback. I held it, and immediately the sensuous presence of the book cast some sort of magic. The book felt both dense and liquid. The cover design bewitched me. I wanted that book more than I had wanted almost anything else. But for me in 1989 or 1990, $15 was an impossible price for a paperback, more money than I’d ever spent on a book in my life. However, that summer I would be working at the bookstore of the local college, and though I didn’t make much money, I did get a 30% discount on books. When summer arrived and I began work, the first thing I bought with my discount was the Vintage Where I’m Calling From.

That copy eventually fell apart. It survived various moves, various weathers, various levels of interest. Its glue dried to dust, its binding cracked in multiple places, pages came loose, pages fell out. On some move or another, I made big sacrifices of books, and one of the sacrifices was throwing out my bedraggled copy of Where I’m Calling From. I hated seeing it in that tattered state, because I couldn’t help thinking about how beautiful it had once been, how broken it was now. I had also lost my taste for Carver’s fiction, and seeing what had become of the book reminded me of how I felt about his fiction: I had used it up, taken from it what I needed, and now all that remained was a broken hull.

A few years ago, I got interested in Carver again. Probably around the time the Library of America collection of his stories came out, or when Carol Sklenicka’s thorough biography was published. I’d paid some brief attention to the publication of “Beginners” and Simon Armitage’s article about Carver, Gordon Lish, and What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, but ultimately I decided I didn’t much care. Nonetheless, on a whim, I sought out a copy of the Vintage Contemporaries edition of Where I’m Calling From in excellent condition. When it arrived in the mail, it brought me back for a brief moment to childhood and to magic. I reread my favorite Carver story, “Why Don’t You Dance?” It still held a bewitching power.

So Much Water So Close to Home

The first book I read cover-to-cover after finishing my dissertation was Brian Evenson’s Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. It’s part of a series of books from Ig Publishing called Bookmarked, which so far is a series of books by men writing about books by men (mostly, maybe even totally, white straight men, at that). Because of the narrowness of its choice of authors, the series held pretty much zero appeal to me until Brian’s book was published — I tend to buy every new Evenson book, because he’s both a personal acquaintance and one of the more interesting writers in America right now, but I was especially intrigued because I didn’t really associate Brian’s work with Raymond Carver’s, and I was curious what sort of insight he would bring to it.

Here is where I must thank Brian Evenson for returning Raymond Carver to me. Or me to Raymond Carver.

This is a key point from Brian’s book:

I’m not a realist, or rather I don’t care if my work is or isn’t — I’ve made a literary career out of muddying that distinction. That, too, is something that I learned from Carver, even though many of his critics, particularly those who favor his later stories, minimize this aspect of his work. But without this, Carver is a great deal less interesting.

I’d lost interest in Carver over the years because I had lost this insight. Once upon a time, I had read Carver in the same way I read science fiction, fantasy, and horror writers, as well as Franz Kafka, a writer I fell in love with near the time when I also discovered Carver. Soon after discovering Carver, I discovered Samuel Beckett, and I went back and forth between them with joy and pleasure. Later, though, I read what other people said about Carver and what he said about himself. Gritty. Realistic. Unflinching. Without realizing it, I began to let the discourse about Carver replace my own understanding of Carver’s stories. In college, I fell in love with Anton Chekhov, and Carver’s own adoration of Chekhov now grated on me: You’re no Chekhov, I said to him in my mind. Every time one lazy critic or another called Carver “the American Chekhov”, I gritted my teeth.

Carver — or, rather, the idea of him — came to symbolize for me everything I hated about American literary fiction.

Taste abhors a vacuum. It is no surprise to me that my taste and Brian Evenson’s taste are relatively similar in a lot of ways, because what Evenson’s book shows is that we came to Carver with excitement for similar writers: He, too, cites Kafka and Beckett, as well as a writer I would later come to revere: Dambudzo Marechera.

Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is part memoir, part literary meditation. Before he ended up as a professor of creative writing, Brian Evenson did a Ph.D. in literature (with a dissertation that “was a critique of Mikhail Bakhtin that used late eighteenth- and twentieth-century novels to suggest a tradition of carnival that was different from the positive, grotesque celebration that Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World suggested”) and was able to visit the Lilly Library’s Gordon Lish archives, where he discovered what D.T. Max would later report on: Lish edited Carver heavily. In the new book, Brian reflects on this editing at length, including his own experience with Lish, who published some of Brian’s work in The Quarterly and then was editor for his collection Altmann’s Tongue. He writes of his time in the archives:

I felt like I was seeing something that, ethically speaking, I wasn’t sure I should see. Something I wasn’t sure I wanted to see. It’s one thing to say that “Where Is Everyone?” lost eleven of its feifteen pages when it became “Mr. Coffee and Mr. Fixit.” It’s quite another to look at those pages and see the proliferation of scrawled marks in Lish’s hand — to see, for instance, that of the last four pages of “Where Is Everyone?” everything but a line or two per page has been crossed out, with Lish writing in as much as he preserves. It’s quite another to see how Lish has crossed out the last five pages of the nineteen-page original version of “Tell the Women We’re Going” and written in the abrupt ending that you love so well. It makes you feel, well, weird, and if you’re a writer it makes you think, too, about every edit you’ve accepted or rejected, makes you wonder how those edits change you, not only as a writer but as a person. Do they damage you? Do they diminish you?

After reading Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, I went back to Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, a book I’d never read from beginning to end. I’d never been obsessed enough with Carver beyond Where I’m Calling From to really pay a lot of attention to What We Talk About, because back when I read a lot of Carver, I assumed the changes between the earlier books and Where I’m Calling From were minor, and then when I learned that the changes were, in some cases, drastic, I was many years away from my interest in his work.

But then, waiting for Brian’s book to be published, I dipped my toes in What We Talk About… Oh myyy! I’d never read “The Bath”, the Lished version of “A Small, Good Thing”, a story that even when I was reading a lot of Carver I didn’t much like — for years, I’ve thought of it as a perfect example of the strain of sentimentality that a certain species of self-consciously Literary writer/reader is a total sucker for (another example would be Alice Elliott Dark’s “In the Gloaming”). “A Small, Good Thing” stands for everything in Carver’s work that I feel completely alien from, and it’s at least partly my frustration with the reverence with which that story is often discussed that sent me away from Carver. (Similarly, I don’t think much of “Cathedral”.)

“The Bath”, on the other hand, cut me open. It’s not my favorite Carver story, maybe not even in my top 10, but it’s sharp and merciless. Is it more Lish than Carver? More Carver than Lish? Do I really care? No, I don’t care. My pleasure in the story does not change if I imagine the author as Raygordon Carverlish or Gordonray Lishcarver or even just Gordon Lish. While I often think the context of a text is at least interesting, and sometimes highly relevant to how I read (indeed, I think of myself generally as at least as much a literary historian as a literary analyst), here’s an example where the Barthesian death of the author really does feel appropriate: At the end of the day, I don’t care who is responsible for “The Bath”, because it is the text itself that affects me.

Brian Evenson does a good job of sorting through the complexities here. He’s right that anybody who wants to think about the editing of What We Talk About… is likely going to feel a bit uncomfortable with it, both because Lish’s editing is so severe and because Carver seems to have felt that these stories were, in the end, not his own. He doesn’t seem to have had reservations about the stories Lish edited for Carver’s first collection, Will You Please Be Quiet Please?, but when given the chance, such as with Where I’m Calling From, he chose to reprint fuller versions of the What We Talk About… stories. With his next (breakout) book, Cathedral, he stood up for the versions he wrote, which mostly avoided the stringently minimalist style Lish imposed on What We Talk About…. And Cathedral became a hit, selling very well (stunningly well for a story collection) and influencing fiction writers to this day. It’s an easier book to like, and includes some impressive stories, but for me, it’s not, on the whole, as powerful a collection as What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.

A Serious Talk

After making my way through What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, I moved on to Carol Sklenicka’s biography. It’s 500 pages long, but I found it a quick read, because I knew virtually nothing about Carver’s life except that he was an alcoholic, he got sober, he married Tess Gallagher, and he died relatively young. Sklenicka does a nice job of detailing Carver’s day-to-day struggle to become the writer we now know as Raymond Carver. It wasn’t only a struggle against alcohol, but also a struggle against upbringing, against class, against assumptions, against — well, against all sorts of things.

The vague image I’d had of Carver as a person was of an avuncular guy who didn’t talk much. And he was that. But not only that.

For instance, Raymond Carver at least once nearly beat his wife Maryann to death. He smashed a wine bottle across her head:

Cecily didn’t pay attention to Ray’s and Maryann’s conversations until she saw Ray bristle, grab a wine bottle, and strike the side of Maryann’s head. Ray and Maryann ran out into the street. Cecily saw drops of blood on the floor. She followed them outside and found Ray standing on the street. Afraid that he might drive away, she ordered him back to the apartment. With a neighbor’s help, Cecily followed the blood trail down the hill and around the block. Maryann cowered in an alley, her white dress soaked with blood. Cecily half walked, half carried her back into the house and dialed 911. […] Cecily rode to San Francisco General Hospital with Maryann but was sent home. Doctors told Maryann she’d lost 60 percent of her blood through a severed artery near her ear.

As alcoholism consumed them both, their lives were often nightmarish, and a lot of the nightmare came from Raymond Carver’s behavior.

Later, after Carver got sober and successful, he and Maryann divorced. Maryann trusted him when he said he’d look out for her and their children, and so she did not ask for any right to royalties from his work, work that she’d been integral to supporting. Sklenicka makes it abundantly clear that without Maryann, there would have existed few or none of the stories that made Carver famous. He didn’t always pay her the $400/month they agreed on, and he left her $5,000 in his will. When he died, he had $215,000 in his savings account. She sued the estate and settled for another $5,000.

(Raymond Carver nearly killed his wife. He smashed a wine bottle across her head. He severed an artery. She lost 60% of her blood.)

One of the virtues of Sklenicka’s biography is that it returns Maryann to the story of Raymond Carver. Maryann herself also wrote a memoir, but I haven’t yet read it. I don’t know if I will. Maybe. The whole story makes me pretty angry, though. Raymond Carver nearly killed his wife.

It’s easy to see why the question of Lish’s editing of Carver’s stories is fascinating and frustrating. Equally important, it seems to me, is the importance of the two women he married: Maryann Carver and Tess Gallagher. Just as his early fiction would not only not have been what it was without Maryann, but would not even have been written had she not supported him in so many different ways, so, too, would the later fiction be quite different without Tess Gallagher’s support and love.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

What do I make of Carver’s work now?

Paging through Where I’m Calling From recently, I still felt great fondness for it. This is at least as much nostalgia as it is aesthetic enjoyment. But there is aesthetic enjoyment, sentence by sentence, and, often, story by story. On a purely aesthetic level, What We Talk About… seems to me a better book on the whole than Where I’m Calling From (for reasons entirely in line with what Evenson says, particularly in his discussion of “The Bath” vs. “A Small, Good Thing”, but also in his insight that What We Talk About… works best as a whole, as more than the sum of its parts) — but on a gut level, Where I’m Calling From will always be the Carver book I treasure. It’s the one I read before I knew anything about Carver except his name, and it’s the book I had a teenage crush on.

In Where I’m Calling From, “Why Don’t You Dance?” is one of the few stories included exactly as it was published in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. It’s the story Lish cut least. For all their differences of style and temperament, for all the differences in their vision of what fiction can and should do, Lish and Carver seem to have agreed on one thing: “Why Don’t You Dance?” is just about perfect.

One More Thing

It’s difficult to perceive Carver now separate from his influence on generations of fiction writers. Learning that Brian Evenson was writing about Carver led me to rethink and reread Carver after I’d allowed my idea of him to be influenced, and in many ways distorted, by all the talk about him. As multiple people have said, his is an easily imitable style, but without the vision and commitment to the style that Carver himself had, that style, like any style alone, becomes hollow. The portability of the style, though, let it infect American creative writing classes from the 1980s to now. The infection is waning, but plenty of senior creative writing faculty are still members of the generation bedazzled by Carver. The only person I can think of to begin to have as much influence today is one Evenson also mentions: George Saunders, whose style is similarly easy to imitate in a hollow out way. (I think Saunders is given to a similar type of sentimentality as late Carver, and, similarly, I prefer early Saunders over his more recent work. An interesting ideological analysis of American creative writing might result from a study of sentimentality in Carver and Saunders: aside from an easily-identified style, what vision of humanity and society makes these two writers so popular among a certain strain of teacher and student?)

But when I think about the influence of Carver, I also think about Lish. In many ways, this helps separate the two men in my mind, because it seems to be the later Carver that has had a more sustained influence rather than the Carver of What We Talk About…, for while the idea of Carver as a minimalist has survived, the actually minimalist Carver (as created by Lish) appears, in my purely subjective judgment, to have had less staying power. This is not surprising, for reasons Brian Evenson makes clear in his book: the early Carver is a vastly more unsettling, discomforting writer than the later Carver.

Lish’s influence on American fiction, both its writing and its evaluation, is indisputable. I don’t know of another editor in the last 50 or 60 years who has been more influential on literary fiction, particularly short fiction, though the influence is not always clear, as it is now so dispersed. (I’ve written about this before, with examples.)

But there’s one influence on Carver and Lish that Sklenicka and Evenson both discuss, and it was a revelation to me: James Purdy. Of course! Given Purdy’s penchant for grotesquerie, it’s easy to see how the connection might seem odd, but not if we listen to the rhythms of Purdy’s sentences and dialogue or pay attention to how he structures his stories or how he handles physical description. Lish told Sklenicka that when editing Carver, he was under the influence of two writers: Grace Paley and Purdy. The mix makes sense. (I must admit, I think Paley and Purdy are both significantly superior writers to Carver overall, writers of greater breadth, feeling, and imagination.) Evenson writes that “Lish must have admired Purdy’s economy of style, his precise control of language in the stories of Color of Darkness and Children Is All, and his ability to conclude stories without the dramatic finality of most of his contemporaries.” Indeed. One of the things, too, that appeals to me in Carver’s first collections is that the worldview seems closer to that of Purdy than his later work does.

After reading Brian Evenson’s book, after revisiting some of Carver’s fiction, I then turned to Purdy’s Complete Stories. I’d read some of his novels and admired them, but I’d only ever read a couple of his stories, and they hadn’t made a deep impression. Now, though, I devoured them. I’m not a fast reader, but within days I’d read at least a third of that big book. While it had been fun to revisit Carver, it turned out that Purdy’s fiction was what I needed.

But that is a story for next time…