Harry Houdini began his 1924 book A Magician Among the Spirits (likely written for him by his assistant Oscar Teale) with a confession:

From my early career as a mystical entertainer I have been interested in Spiritualism as belonging to the category of mysticism, and as a side line to my own phase of mystery shows I have associated myself with mediums, joining the rank and file and held seances as an independent medium to fathom the truth of it all. At the time I appreciated the fact that I surprised my clients, but while aware of the fact that I was deceiving them I did not see or understand the seriousness of trifling with such sacred sentimentality and the baneful result which inevitably followed. To me it was a lark. I was a mystifier and as such my ambition was being gratified and my love for a mild sensation satisfied. After delving deep I realized the seriousness of it all. As I advanced to riper years of experience I was brought to a realization of the seriousness of trifling with the hallowed reverence which the average human being bestows on the departed, and when I personally became afflicted with similar grief I was chagrined that I should ever have been guilty of such frivolity and for the first time realized that it bordered on crime.

It was quite early in his career that Houdini and his wife Bess used Spiritualism in their act, but even though it was popular, he quickly regretted it, disturbed by how credulous audiences were. Even during the time he was performing Spiritualist effects (séances, channeling), he was also occasionally performing entire shows devoted to debunking. He learned something similar from both types of performances: people’s sense of what was real and what was not depended far less on what he, the performer, asserted and far more on the assumptions and beliefs each audience member brought with them. This, he discovered, was true regardless of education, class, or expertise. Sometimes Ivy League scientists, certain no-one could hoodwink them, were the easiest to fool.

Spiritualism originated with the Fox sisters in Rochester, New York in 1848 and quickly became a significant philosophical and religious force in the US, its attraction heightening after the Civil War and then again after World War I — times of great grief when people were comforted by the Spiritualist message that loved ones live on after death and may contact us from beyond.

Spiritualist debunking appeared from the beginning, both from figures representing established religions that saw Spiritualism as a threat and from people of a scientific mindset who either rejected the premises of Spiritualism outright or who were interested in the experimental possibilities that Spiritualist events offered. It wasn’t that debunkers always thought that mediums were fraudulent. There was no great consensus on that — indeed, as R. Laurence Moore pointed out in a 1972 article for the American Quarterly, “If those in the anti-spiritualist camp had cried fraud with a unanimous voice and turned away, their attacks would have killed the movement. But … they witnessed puzzling things which needed explanation. Many persons who thought it nonsense to speak of spirits still accepted the fact that tables in some unaccountable manner rose off the floor. Many fervent anti-spiritualists were at the same time fervent believers in clairvoyance and second sight. Spiritualism was only one of several explanations of the manifestations associated with mediums….”

Spiritualist spectacle also became a significant form of entertainment, especially via the efforts of magicians like the Davenport Brothers. And if Harry Houdini knew anything about anything, it was spectacle.

In his excellent biography of Houdini, Kenneth Silverman writes that the origins of Houdini’s escape act lay in Spiritualism — by the 1870s, Spiritualists were performing greater and greater feats in an attempt to keep the public’s attention, including a wide variety of escapes, not the least of which were handcuff escapes. “By the time Houdini started out, in the 1890s,” Silverman writes, “he encountered a public familiar with mediumistic handcuff tests, if not by experience at least through the press.” Houdini was also quite familiar with the Davenports’ performances. His great insight, though, was to take his act in the opposite direction. He would do escapes (including from all sorts of handcuffs, dubbing himself “The Handcuff King”), but he would insist on these escapes as feats of natural cleverness and athleticism, unaided by the spirits. As Silverman, among others, has shown, Houdini hitched himself to a new cult of active health, strength, and masculinity, setting himself apart from the passive mediums so often seen as delicate, fragile, and feminine.

Houdini’s determination to debunk Spiritualism is sometimes said to begin after the death of his beloved mother in 1913, but this is quite false. He was giving public performances designed to reveal mediums’ methods as early as January 1897, even earlier than he and Bess performed séances in Kansas. (Houdini’s childhood friend Joseph Rinn became a fierce opponent to Spiritualists, devoting far more time to this than Houdini did until after World War I, and Rinn’s book Sixty Years of Psychical Research is an exhaustive and sometimes exhausting account.)

Magicians who did not make their livelihood from performing quasi-Spiritualist routines were often some of the most effective debunkers. It was good publicity for them, as Houdini found, and magicians with knowledge of the ways of con artists were especially good at seeing through the tricks of mediums — magicians who had learned their craft alongside gamblers and swindlers tended to be the best investigators. (For methods of fraud, see David P. Abbott’s fascinating 1907 book Behind the Scenes with the Mediums.) But all magicians who weren’t profiting from themselves being seen as “mystical” tended to be annoyed by Spiritualism, since its spectacles looked like magic tricks that the performers didn’t admit were tricks. John Nevil Maskelyne was an inspiration to many magicians, and his book Modern Spiritualism: A Short Account of Its Rise and Progress, with Some Exposures of So-Called Spirit Media appeared in the mid-1870s.While he had an interest in investigating mediums throughout his life, it was Houdini’s friendship with Arthur Conan Doyle that seems to have pushed him toward a seemingly monomaniacal obsession with exposing Spiritualism. Conan Doyle was famously a devout, credulous Spiritualist, and this at first did not affect their friendship — indeed, Houdini seems to have been curious about the beliefs of Conan Doyle and his wife. But then came the séance of 18 June 1922, at which Lady Doyle filled pages with automatic writing supposedly from Houdini’s mother. Houdini was having none of it: the words were in English, a language his mother didn’t speak, and included such things as cross symbols, an unlikely religious icon for a rabbi’s wife. The use of Houdini’s mother by Lady Doyle, the obvious falsity, and Sir Arthur’s insistence that not only had they shared a supernatural experience but that Houdini himself was a medium … it was all too much. By the fall of 1922, Houdini had reached the limit of his friendship. He just couldn’t bear it anymore, and it seems to have endlessly bothered him that a friend he had so respected could be so insistently gullible.

And then came Margery.

My thoughts here are caused by having just finished reading David Jaher’s 2015 book The Witch of Lime Street: Séance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World. It’s a thoroughly-researched, accessible, popular history. Jaher is objective in his presentation of the story, allowing the events and personalities to speak for themselves. This is vitally important — and tremendously difficult — for a narrative of magic, skepticism, and Spiritualism. Much of the history went unrecorded or deliberately obscured, and everyone involved had an axe to grind, a reputation to uphold, or a belief to protect. As readers, we want history to be clear, its ambiguities smoothed by the sands of time, and sometimes it is, but just as often time has sanded away the details necessary for any definitive judgment. We can, for instance, speculate about the methods William Mumler used to create his spirit photographs, but the actual process and his motivations died with him.

It’s the same with the case of one of the smartest, most talented and/or cunning mediums ever to have been investigated. I expect some readers who want to take the side of either Houdini or Margery get frustrated that Jaher does not tip the scales in their direction. I think it would be a less compelling book if he did.

Her name was not Margery, any more than his name was Houdini. She was Mina Crandon, third wife to Dr. Le Roi Goddard Crandon, a wealthy Boston surgeon. Scientific American magazine had offered a substantial reward to anyone who could provide convincing evidence of actual mediumship. They brought Houdini in on some of the investigations. One after another candidate proved easy to debunk. Finally, they heard about a woman who lived on Lime Street in Boston’s upper-class Beacon Hill neighborhood, a woman they would dub “Margery” (at her request) to protect her identity. Sure enough, test after test befuddled the scientists. They began to think they might have found the real thing. A few were completely convinced. The doubters had no good explanations for the feats Margery performed. Eventually, they called in Houdini.

The story gets complex. Jaher does his best to keep it lively, but he is also committed to representing the history accurately, including how relentlessly repetitive it all was. It’s important that he lead us through one test after another because it is important to see just how much Margery went through. It’s perilous to psychologize her now, almost 100 years after the events, but it’s hard not to come away with a sense that despite the many investigations, Margery seemed to enjoy her ability to confound the experts. Despite her initial demurrals, she soon encouraged the attention both of prominent men and of the world at large. She may not have loved the idea of attention and fame, hence her desire to hide her actual name, but once “Margery” became as recognizable a name as “Houdini”, she seemed to want to hang on to the spotlight. (Certainly, her husband did. It’s clear that he pushed her at times beyond where she wanted to go or what she wanted to do. But there’s no great sense that Margery was an unwilling participant generally.) Her encounters with investigators and with Houdini in particular were chronicled at great length throughout the world’s press and in various books, including one of Houdini’s own last publications, the pamphlet Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by the Boston Medium “Margery”….

The historical record is rich with depictions of Margery. The chronology and events can all be determined. But what they mean, what they add up to, what they suggest … that is much more murky. And a lot depends, even now, on what you are willing to believe.

In A Magician Among the Spirits, there’s a rather disappointing chapter titled “What You Must Believe To Be a Spiritualist”. It’s disappointing because it’s too particular — Houdini lays out one outlandish event after another. More interesting would be an exploration of belief generally. To be a Spiritualist, you must believe in the possibility of an individual personality and memory surviving after death. While such a belief is hardly unique to Spiritualism, it is definitive. In other religions, you can probably lack a strong belief in the survival of individual personality and memory after death and still believe strongly in the religion, but with Spiritualism, it just won’t work. The fundamental doctrine is that death is a transition that individuals survive and that those individuals are able to connect to the world of the living via mediums.

Spiritualist beliefs did not pop out of nowhere like ectoplasm. In Spiritualism in Antebellum America, Bret E. Carroll provides a concise lineage:

Like Unitarianism and its offshoot Transcendentalism, [Spiritualism] absorbed Romanticism’s emphases on a loving deity, the inner divinity and consequent goodness of the individual, and gradual spiritual growth into divine perfection. It shared with Universalism the belief that a loving and merciful God must save everyone, and with its schismatic Restorationist offshoot the qualification that some period of postmortem repentance and punishment would precede redemption. It incorporated the Quaker emphasis on the importance and validity of each individual’s “inner light.” It derived from deism and the Enlightenment a belief in a “natural” religion that conceived deity in terms of the natural law discovered by science and reason. At the same time, it preserved much of the traditional Christian emphasis on divine sovereignty and theocentrism, human dependence on the divine, the reality of immortality and an afterlife, and a moral obligation to order one’s life in conformity with an absolute standard.

No one Spiritualist belief is especially “weird” in the sense of being alien to other belief systems. Countless people do believe in life after death and, specifically, the survival of individual personality/memory and the possibility of contact with the dead. If someone believes that, then they may find Margery credible, at least to some extent. If they do not believe in life after death, and specifically do not believe in the survival of individual personality/memory and the possibility of contact with the dead, then they will not be able to believe that Margery was anything other than a fraud of some sort.

The challenge is that history does not provide a definitive answer. Because Spiritualism foregrounds evidence more than other religions do, it can seem like we’re talking about something other than a religious practice, but that’s what it is — a belief system that, for all its actions and events, still relies on faith. There may be plenty of historical facts and events in the story of Houdini and Margery, but those facts and events mean differently for people who share some of Margery’s faith and for people who share none of that faith. That was true in the 1920s and it is true today. While some of Margery’s techniques were accepted as fraudulent by most people who examined the evidence, there were still many people who never stopped believing that at least in the early days of her mediumship she was not a fraud. By most accounts, pro and con, Margery was the most talented and impressive medium of her day. How we let that information settle in ourselves is the question that The Witch of Lime Street ultimately poses.

Margery was very good at what she did. But … what did she do? How much of that question we can answer depends less on the historical record than it does on what we are willing to believe.

(I don’t, myself, believe in the survival of individual personality and memory after death. I have no capacity to believe that Margery or any other medium who claims to speak to or channel specific dead people is doing so. Nonetheless, I find myself thinking that with some mediums there is something interesting going on, something that isn’t quite captured by the label of fraud or deception. I’m not even sure I have words to say what it is that’s going on, just that fraud and deception — while certainly a big part of mediumship [cf. Revelations of a Spirit Medium or M. Lamar Keene’s The Psychic Mafia] — don’t quite capture the most interesting cases.)

From its beginning, Spiritualism thrived at least as much from doubt as from belief. Newspapers and magazines aligned themselves with one side or the other, producing countless pages of coverage from the time of the Fox sisters in 1848 well into the 20th century. Like many religions, Spiritualism called for witness, but unlike most religions, it emphasized evidence. It was, up to a point, committed to empiricism. Its miracles were demonstrable and repeatable. While Spiritualism is often said to be a counter-response to the technical, materialist imperatives of industrialization, It was the perfect religion for an era of scientific progress and inductive reasoning, a religion based on observations and proofs, a religion guided not by bibles and priests but by the authority of one’s own experience. As many scholars have pointed out, Spiritualism and occultism generally fit well with the technological developments of the later 19th and early 20th centuries — microbiology and astronomy offered ideas of vast worlds beyond the visible; telegraphy sent voices across great distances; x-rays provided a method for looking through solid objects…

It was also a path by which people who were marginalized or, in many cases, explicitly prohibited from speaking could find a voice and could be heard. The importance of Spiritualism for women’s rights has been highlighted at least since Ann Braude’s now-classic book Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in 19th Century America, whichargues that “In mediumship, women’s religious leadership became normative for the first time in American history.” Braude highlights the way Spiritualism, and mediumship in particular, allowed women to conform to the social strictures of the time while also asserting autonomy and power — in effect, escaping the bonds of patriarchy and tradition without the audience noticing. “…Spiritualism,” she writes, “made the delicate constitution and nervous excitability commonly attributed to femininity a virtue and lauded it as a qualification for religious leadership.” She notes that the medium remains passive; it is the spirit that is active. The medium is a messenger, a vessel, not to be blamed for the actions and words of the spirit from beyond. This had wonderfully transgressive implications.

We see the transgression in Margery. The spirit she channeled was always her deceased brother, Walter, who was saucy and unpredictable, who spoke with far more vulgarity than Mina Crandon allowed herself. Part of the success of Margery the medium was the vividness of the character of Walter. This comes through beautifully in The Witch of Lime Street. “Possessed by Walter,” Jaher writes, “she did and said things that would otherwise have been off-limits in this man’s city, where a woman could neither enter most speakeasies nor sit on juries. A society wife was not supposed to swear or smoke — yet Margery, while believed to be unconscious, channeled a coarse and irrepressible spirit control.” Mina Crandon may have been strapped to a chair, but Walter was unfettered, defiant, insulting, and fun.

In a 2013 interview, Crandon’s great-granddaughter said, “I think one thing that has gotten lost in the written history is that what she produced in the séances was often quite beautiful, and fun. She took on an intellectual challenge and certainly gave the investigators a great show. I would like to think that she derived some sense of satisfaction from that.”

The fun of it comes through vividly in Jaher’s narrative. As he tells the story, we get a sense of Mina/Margery enjoying herself — enjoying the freedom fo speaking as Walter and enjoying the achievement of confounding a bunch of eminent men. For years, she was subjected to an exhausting array of tests, some of them undoubtedly physically taxing and likely even painful, and she kept asking for more. It was as if she was showing the men that no matter how much they confined her, she would be free.

Margery (and Walter) obviously enjoyed taunting Houdini particularly. She was clearly fond of Houdini, and how could she not be? He was her best adversary.

What also comes through in Jaher’s telling of the tale is how the men who test Margery are afraid of, ignorant of, and also obsessed with women’s bodies. From the early years of Spiritualism, men made accusations that mediums were trying to seduce them or seduce other people at a séance. It’s hardly surprising: in a buttoned-up society, séances put women and men together in dark rooms. Women who were mediums certainly had to fend off the roaming and sometimes outright assaulting hands of men. Some investigators particularly enjoyed the apparent permission their position gave them to “inspect” women’s bodies.

Throughout the investigations of mediums, including in Jaher’s book, there’s a lot of talk of orifices and how women can hide … things … in the most private areas of their bodies. It’s both comical and disturbing. And yet, there was sometimes cause to raise the question. While a couple of the less knowledgeable men investigating mediums seem to assume a woman can hide a whole table in her vagina, it’s true that some mediums did hide small items in places where men were unlikely to examine closely. Houdini had previously investigated Eva C., who famously “birthed” ectoplasm from her nether regions.

There’s a photograph of Eva C.’s vaginal release of ectoplasm in the excellent book The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult — a particularly powerful exploration of Spiritualism because Spiritualism and photography grew up together and each in their own way brought metaphysical questions into popular culture. (For more on the history, see Peter Manseau’s The Apparitionists.) Photographs proved both helpful and detrimental to mediums and skeptics alike, as Andreas Fischer chronicles particularly well in an essay in The Perfect Medium. Mediums who produced materializations (ghosts, objects, ectoplasm) were attracted to photographs as proof of the reality of their claims, while skeptics thought the photographs showed how ridiculously obvious the fraud was. People ultimately saw what they believed they saw, or what they wanted to see, whether in life or in photos — skeptics were astonished that anybody could be taken in by what the photographs showed, while some collections of testimony and photographs, such as Albert von Schrenk-Notzing’s Phenomena of Materialization, caused what Fischer calls “a real epidemic of materializations” as mediums got inspired by each other.

Spiritualism still exists, though it rarely looks like it did 100 years ago. (For images from nowabouts, see Shannon Taggart’s astonishing art book Séance.) The religion began to decline in popularity in the United States and UK in the 1930s. Jaher writes: “Spiritualism, as it turned out, had more appeal for the bereaved than the bankrupt. By 1930, in the wake of Wall Street’s crash, public interest in the Quest Eternal was waning. In that year William McDougall and Joseph Rhine founded the Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University, effectively taking psychic research out of the séance room. Rhine’s experience with Margery had contributed to his mistrust of any case that savored of ghosts and spirits. The reign of the physical medium was over as far as he was concerned.”

Or … not.

We have never been disenchanted. New Age religions in many ways took the place of Spiritualism, signalling the triumph of perhaps its greatest competitor, Theosophy, one of the most direct precursors to a lot of the scattered beliefs and practices that get the New Age label. (I continue to believe that the 20th century was as deeply influenced by Madame Blavatsky as by Marx and Freud.)

After reading The Witch of Lime Street, I realized that I had some dissatisfaction with the book, but it was not David Jaher’s fault. Mina Crandon, the woman behind Margery, still remained something of a mystery. Houdini diligently documented his life and opinions. There are things we don’t know and will never know about him, but he feels historically knowable in a way someone like Mina Crandon does not. We will never know what she was thinking, never know how she perceived herself, never know what she truly believed, intended, or desired.

We need, I thought upon closing Jaher’s book, a medium for Mina.

Or, rather, we need the kind of medium I most deeply believe in: a fiction writer. The unique property of fiction is that it can bring us into the minds of the dead (and of the never-existed). Many artists have been drawn to some element of Spiritualism, occultism, or esotericism because the experience of making art can be an experience of possession and channeling. I find the life of Hilma af Klint so compelling, her art so powerful, not because I share her beliefs in spirits and Anthroposophy but because within the context of art her beliefs don’t seem particularly odd to me. For me, unlike af Klint, talk of spirits and possession is more metaphorical than real, but I’m not sure, when it comes to art-making and inspiration, that the difference matters much.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking it would be interesting for someone to write a novel about Mina Crandon. It would take a supremely talented fiction writer and a particularly sensitive person to help us imagine our way back to Margery.

Magic, whether real or imaginary, always teaches us the value of imagination and the necessity of wonder. (I am a fiction writer, but whatever talents I have are not at all up to this task. It’s a book I yearn for as a reader, not one I yearn to write.) Now having spent a lot of time with the actual history of Spiritualism, of Houdini, of psychic investigators, and of Mina Crandon, I yearn for more imagining.

—–

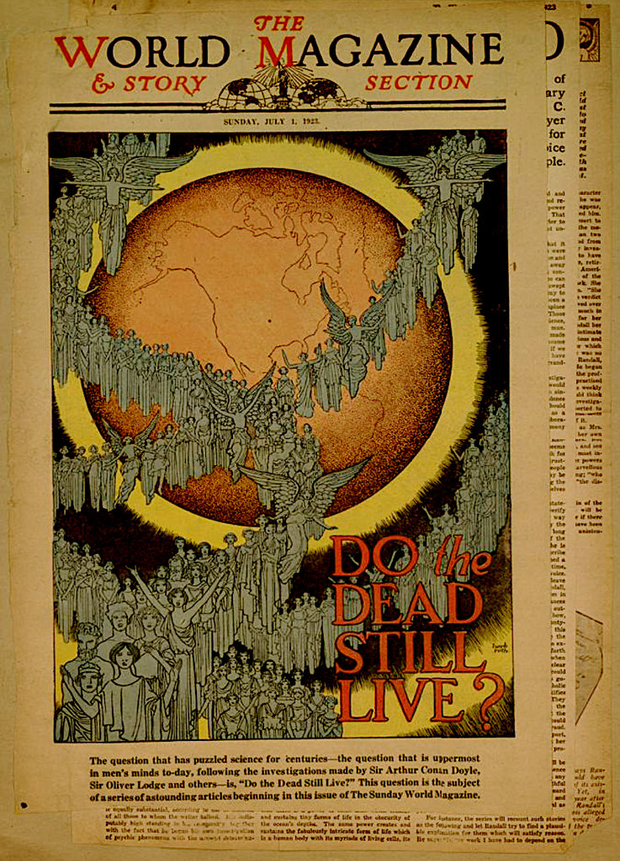

images: 1.) From one of Houdini’s scrapbooks, now at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. 2.) Weird Tales, April 1924. 3.) The Witch of Lime Street cover. 4.) Mina Crandon, 1924, via Wild About Harry blog. 5.) “The Fox sisters: They demonstrate their ability to levitate a table, to the Reverend Hammond, who is suitably impressed.” 6.) Houdini and Mina Crandon, 1924, via Potter & Potter Auctions. 7.) “The medium Eva C. with a materialization on her head and a luminous apparition between her hands,” 17 May 1912 by Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, via Wikimedia. 8.) Leonora Carrington, “Evening Conference”, 1949, via The Guardian.